Behind the scenes with: England U18s

RCW editor Dan Cottrell studies the coaching methods of those charged with developing the next generation of England players, namely Jon Pendlebury, the England U18s head coach, and Will Parkin, his assistant. Dan outlines his eight key takeaways and what coaches at all levels can learn from the elite.

I was lucky enough to be invited to watch an England U18s training session, as they were put through their paces before their tour to South Africa, writes Dan Cottrell.

A total of 26 players and nine staff would be travelling to play three internationals, against Ireland and Georgia, as well as the home nation.

Jon Pendlebury, the England U18s head coach, and Will Parkin, his assistant, shared their thoughts and intentions regarding the direction training was taking.

There is so much all coaches can take from these sessions, even if we take into account I was watching the 26 best boys from England.

I looked at how simple the exercises were, when they are used, why they are used and the intensity and accuracy required.

Here are the eight key lessons I took away from my observation that I think coaches at all levels can use.

Be prepared

There are two themes around being prepared.

The first is how players experience international rugby and understand what the expectations will be.

This is to ensure that there won’t be many surprises if they get the opportunity to step up to the next stage, which might be an U20s game in the very near future.

For example, running out in an away game in France, with the home crowd at their noisiest, is to enter a cauldron of emotions. No training session can replicate that atmosphere. Any of the U18s who play in that game will be in better shape for next time.

This goes for routines and expectations. The morning I was there, four players missed a meeting time. They were lightly admonished this time and told that the U20s coaches would be more demanding.

The coaching group was keen to ensure that more experienced players helped less experienced ones with their preparations. For example: What do they need to know for training? What were the expectations about behaviour?

The second theme was about being prepared for the training session itself. We will look at that in the session design points.

DAN’S KEY TAKEAWAYS

-

How can you help less experienced players feel their way into more stressful situations?

-

For matchday experiences, if a player can’t be on the bench and have some game time, they can shadow the team, perhaps acting as a water-carrier on the day.

-

Buddy systems, with more experienced players taking on a mentee, are a tried-and-tested method. Often, this is done informally, but an intentional plan with clear objectives is good.

-

Good mentorship builds good mentors for the future.

Pre-session information

With so little time on the training field, it is essential to make the best use of the available resources. Even at this level, there isn’t as much time on the grass as you might think.

There was an indoor meeting before the outdoor session started. Prior to that, the players were sent some video clips to study, which focused on the plays the team were going to implement.

While there is structure on the pitch, the philosophy is that ’speed trumps structure’. In other words, everything should be done at speed, and, if the ruck ball is quicker than the players are at getting into their shape, the team plays anyway. The attack can’t give the defence the chance to reorganise.

Part of the speed comes from knowing the specific roles inside the structure.

The players studied footage from a lineout in a particular part of the field. It showed them running through the play in a previous training session, but it could, equally, have been from any team or any match.

This footage was replayed during the indoor meeting. The players, sitting in groups of similar positions, talked through where they should run and where to be from the subsequent phase.

For example, the last player in the lineout, who might have initially bound on to the side of the maul on the openside, would know that the backs might attack in the 13 channel.

The group would explore decisions based upon who carries when and where, and where that player from the maul may reload to attack for the next opportunity.

From these pre-set positions, the key decision-makers could look up, see where the defence was weakest and know where they could attack, with the confidence that they had options.

When the second phase of play unwinds, the video revealed how the timing might work. Some players might have been too deep, not engaging the defence if they were to be decoys.

Will Parkin asked the following questions to the group:

- What pieces of information do you need to know to run the play?

- How can you engage the defence here?

Players need to take ownership of the plays and the details in execution. For example, there was footage from games where it was clear when good footwork helped achieve better outcomes, or when an arriving player needed to latch onto another supporting player.

It was interesting that they discussed decisions around going in to support the breakdown, and the consequences on the next play.

For example, if the 13 had to resource a breakdown, that might change the angle of the next attack, because the shape of the attack was different.

Overall, while every phase of play aims to bust the line, players need to know what might happen next if it didn’t.

In this vein, playing out of your half from a set-piece might mean organising a good chase from a kick. A good chase needs the speedier players to be on their feet. It also depends on whether the kick is from the 9 or the 10.

Aligned with the philosophy of speed, this team was challenged to run/pass/kick from rucks and mauls in play, and explore what opportunities it created or forced.

The quicker into position in attack, the more likely you are to find a disorganised defence.

If this is the principle, it still needs planning.

DAN’S KEY TAKEAWAYS

-

How much information can you share ahead of a training session? The first issue is whether the players will actually look at it. In that case, you can have two tiers of information: the first is need-to-know, and the second is nice-to-know.

-

What information would be helpful? Reminders of shared language, a play you’ve been running through, and perhaps a clip of a play or passage of play.

-

Make the information valuable at training. Challenge players on what they saw or thought about. Do it in groups, probably of similar positions.

-

When should you review the information? You can meet in the changing rooms before training. Five minutes here could actually give you more time on the field, because the players know what they are doing and why, and will have been part of the process of organising the plays.

-

Knowing a role, especially in supporting the next phase, can be explained away from the training session. Then, when the play is being introduced or reviewed on the field, the player might be able to understand what is happening and self-correct if they are out of position.

- Structure is a rule of thumb. It helps create a shared understanding of where to be and why during the first few phases after a set-piece. But, at a ruck, if the ball is available quickly, it should be played quickly. The potential cost of not being in a position to attack is often outweighed by the benefit of attacking a defence that is not yet set.

EMBEDDING PLAYS, PRE-SESSION

- Video clips are sent out and players are told what to look for

- Indoor meeting: The clips are replayed and players are asked what pieces of information they need to know to run the play

- Outside session: Walk through the play, then do a semi-opposed run through

’Selling’ and ’drama’

During my visit, I often heard terms like ’sell’ and ’drama’.

A ’sell’ is a gambling term for creating some misdirection. In rugby terms, you are ’selling’ the opponent one picture, while actioning another.

For example, in a ’blocka’ play – where one runner attacks towards the ball, but the passer pulls the ball behind that player – the runner must ’sit down’ the defender.

A good sell comes with ’lots of drama’. The defenders will be convinced that the play is coming their way, adjust themselves and prepare, creating the next hole.

Both Jon and Will were keen to follow through on one technical point: not stopping to pass.

When an attacker slows down to pass, the defender marking the ball carrier has a chance to move. This is especially true if your team is using pull-back passes.

An attacker who has just passed the ball, but remains moving forward, still engages the defender for a moment or two longer than if they had slowed down, and might even block that defender’s line of sight or support lines.

DAN’S KEY TAKEAWAYS

-

Every attacker needs to think about engaging defenders. While running straight is the standard way, what else can the attacker do to make the defender prepare themselves to tackle them? Examples include calling noisily for the ball, running an angle (sometimes known as a hard line), or shaping the hands and body to receive the ball.

-

In training, touch rugby doesn’t help players perceive a gap in the defence, because fingertip tackles don’t give the right impression. Use shoulder-on tackles, where the tackle isn’t completed, but if the shoulder makes contact, the ball carrier must go to the ground. Use ’bib-touch’ as another way to create more realistic defences. Now players can see the consequences of their ‘sells’ and ‘drama’.

-

Even in unopposed training, encourage players to think about creating the next hole, so they are aggressive in their movement.

-

Passers should not stop to pass.

Skills to win

Jon pushes the principles of Speed, Attachment and Space (SAS) and these are constantly emphasised by the whole coaching group.

This feeds into the skills that the players are constantly tested on. While they arrive with plenty of training hours under their belts, the U18s camps aim to hone the basics, so they can perform them at speed and under pressure.

There are three main focuses: ball movement, ball carry and low-aggressive tackling.

The breakout drills were basic. The intensity and attention to detail were not.

It is essential to note the context of what Jon and Will were aiming to achieve. Because the team were travelling the next day, they knew the players would be extremely nervous about picking up a knock or a concussion that would rule them out of the tour. With plenty of new caps, this exacerbated their anxiety.

Consequently, execution wasn’t quite at the levels you might expect. However, in the early part of the session, a PA system played music from the players’ playlists to help reduce the stress.

I will discuss the skill details in the next section, but the language was clear and agreed upon by all. The players knew what was being said and why.

Will was one of the feeders for some of the passing drills. This allowed him to change the pace of the activity. It also meant he was, in a sense, inside the activity, which meant he could give really hot feedback close-up to the players.

Here are some examples of how Jon wants to employ SAS:

- Speed: to play, to reform, to scan, to set for the next play.

- Attachment: connect in defence, support and communicate together.

- Space: where to score, reduce for the opposition attack, create and exploit.

DAN’S KEY TAKEAWAYS

-

What is your team’s playing philosophy? It might just be two words, like Speed and Attachment. These are used to give skills and tactics more meaning. The players have a ‘why?’.

-

A philosophy won’t work unless everyone takes some responsibility for it. It should be a constant in the session and games. Players should be prepared to be called out and call out others if this isn’t being executed.

- To enact your message, sometimes you need to be inside the session. Acting as the feeder gives you this opportunity. There’s a balance, though. Being close gives you a player’s eye view; being detached allows you to see the whole.

Related Files

Passing detail

Short passes need detail – and much of that detail applies across all passes.

Will was keen to ensure that the passers in the exercises...

- Stayed square: That fixes defenders and creates holes.

- Kept their feet moving: And didn’t stop to pass. Again, that fixes defenders and, potentially, blocks them, too.

- Didn’t lean back: Some players tended to lean backwards when they delivered long spin passes. This reduced accuracy, because the wrists had to compensate for the wrong arm angles.

Will wanted the players to avoid flicking the ball for short passes, which is where the receiver pats the ball on to the next player. A deliberate catch, run and pass are needed to hold a defender, though this can still be done quickly.

The team practised the details in five-minute bursts.

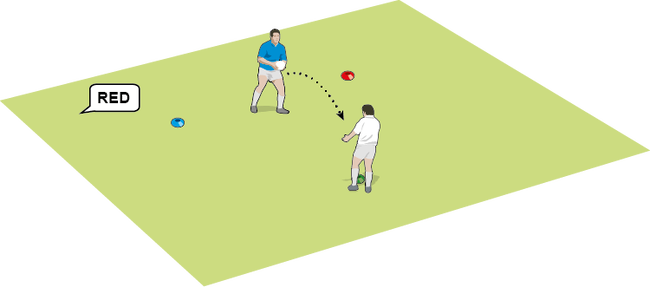

The first was a simple three-player passing exercise. A coach, acting as a feeder, passed the ball into the line of players, who were no more than 1m apart. They had about 5m to run and pass. The last player popped the ball to the feeder, who fed the next group running the other way.

The second exercise again had the group set up in threes. This time, the feeder stayed on one side. Two players were opposite the first two receivers, leaving the third player ’in the hole’. There was about a 5m gap between attack and defence.

Once through, the last player popped the ball to a coach, who passed it back to the feeder. The first two passers turned and became defenders. This led to a high-intensity pressure exercise, focusing on catch, run, and pass while staying square.

Later, the backs moved into a two-pass exercise. Again, the ball was fed in from a feeder, normally a coach.

The first receiver took a short pass and pulled the ball back to a trailing runner, who had started behind them.

The second receiver ran, initially, diagonally, before squaring up to deliver a long pass to the final receiver, who ran forward and popped the ball to another feeder, who would pass to the next group coming forward.

This worked on passing from left to right. After a couple of minutes, the passing direction was changed. The emphasis continued to be on getting square, running to pass and not leaning back.

The success rate was around 75%, with a few longer passes dipping or going behind the receiver. This is a good ratio in skill acquisition, and shows the exercise was on the edge of the difficulty range.

If you are about to go into a game, reduce the distances to heighten performance confidence.

Overall, it was crucial that players made decisions based on what is going on in front of them. All the exercises built towards this because, ultimately, this is what the coaches wanted the players to do.

DAN’S KEY TAKEAWAYS

-

Work on technical detail in every session, but for very short bursts. If exercises are all familiar to the players, they concentrate on the skill, not the drill.

-

Not every drill needs a decision. Sometimes, the players must retrieve and become more confident with a movement. Then, it can be put into a more pressurised exercise.

-

The 3v2 exercise was not a decision-making activity. It was purely to pressure the players to execute the skill under pressure.

-

In some activities, you are looking for a high level of success; in others, you might expect more mistakes. It is worth telling the players beforehand what your expectations are.

-

The more the players know the context of an activity, the more likely they will engage with what they are doing, and transfer this into the game. In the England session, the 3v2 was very much about ’space’ and ’the next hole’.

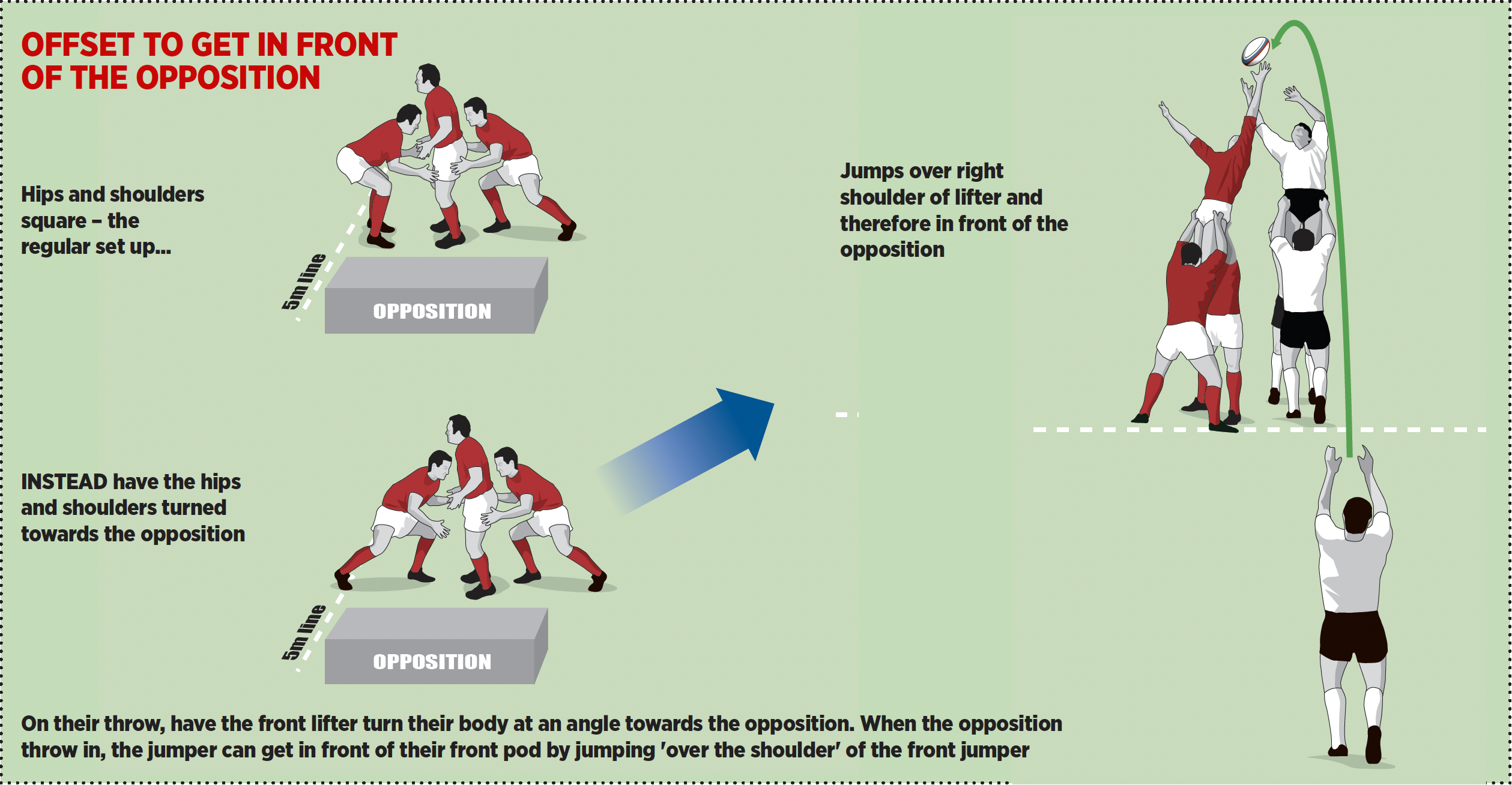

Slow-motion walkthroughs

After the strength and conditioning team had warmed up the players, the backs and forwards split.

The forwards walked through their lineouts, while the backs went through plays they would be running in certain areas of the field.

There are two key points to consider here.

The first is that they were walkthroughs, which were really at jogging pace. The plays were either new, or undoubtedly not familiar, to all the players.

To enhance learning, the coaching group recognised the need for slow thinking time, so the players could process all the information.

The session can be sped up once the players are comfortable with their roles, running lines and shapes, but not in this section.

The slow pace gave plenty of chances for the players to give and receive feedback. I was with the backs for most of this part; the backs coach, Will, directed the play and explained why it would work. It was a mix of instructions and questions.

Everything was run as a scenario, and Will acted as the forwards. From a set piece, he would release the ball.

The play would unfold to one part of the pitch, and then, in the next phase, he might call for the ball, or it might be another back’s ball.

If he received the ball, he might go forward, sideways or backwards. At a jogging pace, the backline would adjust accordingly and choose the option depending on whether the ball was going forward or slowed down.

The plays could then unfold, with the players gaining more understanding of their running lines. With five spare backs, a reasonable defensive line could offer some context.

The second key point is that the plays had already been discussed, and mentally walked through, before the session.

I asked Will how many plays came from coaches and how many came from players. It was a balance, based on feedback from previous sessions and games. Will had met with the key decision-makers in the backs to come up with the plans.

Talking to Jon before the session, he was keen to emphasise that they needed to think about how much the players could learn in the time they had with them. Too much information would simply lead to lots forgotten very quickly.

Walkthroughs were one way to reduce this learning stress.

DAN’S KEY TAKEAWAYS

- New plays and even new drills benefit from a slow-motion start. This could be walking through what’s going on. It is about where players must be, not how they execute their skills. Once things speed up, the players must adjust their timing, but they will at least know where they should be.

- Walkthroughs also give everyone a chance to understand the ‘why’. This is more likely to engage players because they know where it fits into the game plan.

- Varying the second or third phase starting point, and the speed of delivery, means that backs plays can be tested out with different options, based on that context.

-

If there are no extra players to act as defenders, using a line on the pitch as the tackle line is a good way to give the attack a target.

-

Walkthroughs give some idea of what perfect might look like. When it moves up to game speed, the players need to know what to do if things don’t go to plan. This can be spoken about in the walkthrough.

Slow down the breakdown

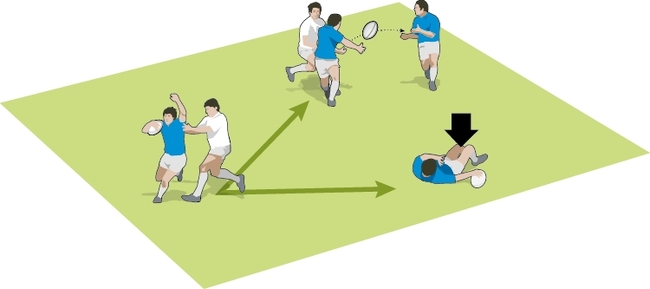

One of the challenges in training games, where you are trying to run through your playbook, is creating a realistic outcome when you are not playing 15v15.

Jon told the players that, if they find themselves in lots of space due to an unlikely overload in attack, they shouldn’t sprint ahead for the glory, but go to ground as if they had met some opposition.

In closer quarters, they told the ball carrier to slow down before contact, which might create a bit of a wrestling situation with a defender. This causes enough disruption to replicate the speed of the game.

Sometimes, the ball carrier might face two defenders, and the wrestle would take longer.

Though it didn’t happen, Jon suggested he might indicate to the 9 when the ball was slowed down.

Overall, it is easy to look good going forward all the time in semi-opposed rugby. However, players need to reload when the contact and ruck speed isn’t ideal.

However, the message was always the same. Speed is crucial to outwit the defence. Being in position quickly not only puts pressure on the defence, it also gives more opportunities to scan for holes.

DAN’S KEY TAKEAWAYS

-

How do you make team runs more realistic? If the players are just reminding themselves of the play, then the speed of ball isn’t an issue. However, if you want to stress the plays – which means players must time their runs or change their decisions – you must find ways to slow down the tackle area. The coach giving a countdown is probably the least realistic, so the tackled player has to create some slowdown as they go to the ground.

-

It is okay to have some form of grab-tackle and shoulder contact if you run plays. These are generally low-level impacts and encourage both attackers and defenders to get into better positions around the contact area.

-

When the numbers are uneven, the attacking team must play their part and recognise that they will have to imagine they are tackled.

-

Let’s remember the purposes of this part of training: to help with timing; to connect some phases of play so players know their roles; and to create possible decision-making options, so the players might have to think about where to attack.

-

Should you expect good execution of core skills? Absolutely, but don’t make it the feature.

Defence to scan

A good tackle slows down the attack. A double tackle can drive back an attacker. A counter-ruck, or even an attempt at a steal, adds to this slowdown.

All of this allows the defence a chance to scan to match up to threats.

Every tackle can create a ruck with two sides to defend and a backfield to cover, so the more time that players have to look up and check that the numbers are correct, the more pressure they can apply on the next attack.

One technical section in this session focused on the tackle, especially the low, aggressive tackle.

The message was: ‘Let’s create time in the tackle to give us time to scan.’ Again, the drill had a technical element that was very much aligned with the reason why.

DAN’S KEY TAKEAWAYS

-

Every technical activity needs a clear context for the players.

-

Tackling shouldn’t be seen in isolation. Making a tackle isn’t enough. Making a good tackle doesn’t just stop that ball carrier, it gives the whole team a better opportunity to win the next phase

BALL CARRY AND BEYOND

The term ’ball carry’ refers to the actions of the ball carrier in and around contact.

Ideally, all players run into spaces. The U18s aimed to create holes for this purpose.

However, the ball carrier will have to take contact during a match, and they must manage that to allow for the best outcomes.

Because this was their last session before flying out, the bone-on-bone work was kept to a minimum, and ruck pads were used to reduce impacts.

Assuming the player couldn’t pass during the contact, the key outcomes were to fight forward and then fight on the ground to place the ball back as far as they could towards their team.

The next player would drive low and beyond the ball. The next one would do the same, but this depends on the defence.

The decision here is whether to be strong over the prone player or drive beyond.

With the emphasis on speed, it was preferable to leave the ball exposed for the clearing passer (the 9) to be able to whisk the ball away.

However, if it were clear that the defence was there in numbers, then it would require more players, with support players anchoring onto the tackled player.

Newsletter Sign Up

Coaches Testimonials

Gerald Kearney, Downtown Las Vegas Soccer Club

Paul Butler, Florida, USA

Rick Shields, Springboro, USA

Tony Green, Pierrefonds Titans, Quebec, Canada

Subscribe Today

Be a more effective, more successful rugby coach

In a recent survey 89% of subscribers said Rugby Coach Weekly makes them more confident, 91% said Rugby Coach Weekly makes them a more effective coach and 93% said Rugby Coach Weekly makes them more inspired.

Get Weekly Inspiration

All the latest techniques and approaches

Rugby Coach Weekly offers proven and easy to use rugby drills, coaching sessions, practice plans, small-sided games, warm-ups, training tips and advice.

We've been at the cutting edge of rugby coaching since we launched in 2005, creating resources for the grassroots youth coach, following best practice from around the world and insights from the professional game.