4 counterintuitive concepts about how we learn

Sarah Cottingham, teacher educator and Educational Neuroscience MA, challenges us on how we think we learn and how we might apply it to our coaching. Dan Cottrell provides the rugby examples.

1 TO INCREASE EXPERTISE, DON’T DO AS THE EXPERTS DO

Putting players in the position where they must "think like an expert" ignores the process of learning that got experts there. There’s no shortcut to expertise. Instead, players need to build rich, well-connected schemas.

Schemas are a generalised set of movement patterns stored in the long-term memory that allows you to adapt to every situation.

To do this, a lot of what players need to do looks nothing like ’expert thinking’.

I like Christodoulou’s (2019) marathon analogy: You don’t start training for a marathon by running marathons. You eat right/sleep right, do short, fast runs and slower, longer ones.

These things look nothing like the end goal. You only run marathons once you’ve done these things.

To execute a skill that will help them solve a game problem, players need a lot of domain-specific knowledge. For example, they need to know how to pass, catch, run to fix a defender and use support lines to solve a 2 v 1 problem in attack.

They don’t learn this knowledge best by attempting lots of 2 v 1s to start with. They do a load of things that look nothing like a 2 v 1: watch modelling, learn small bits of knowledge, practise elements of the 2 v 1, like passing, catching, running onto the ball, fixing a defender.

A 2 v 1 is a relatively simple "game problem". Now think of building this in a more sophisticated game plan where you want your players to realign to attack more effectively. Expertise comes from building the elements, not going to the finish point first and replicating the best teams.

2 PLAYERS’ PERFORMANCE MAY NOT BE A GOOD INDICATOR OF LEARNING

Learning is a long-term process.

If you’ve taught something new and players perform well on the task, that doesn’t mean it’s been learned. To infer learning, we need to check over the long term.

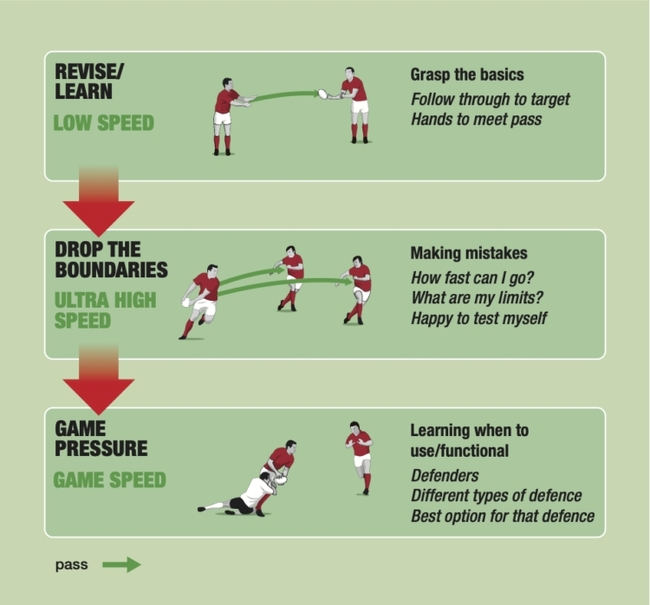

Also (and what could feel more counterintuitive than this), conditions that impair performance in the short term can improve learning in the long term...and conditions that make performance improve quickly often fail to support long-term learning (Bjork & Bjork, 2020).

Use techniques that slow performance yet improve learning like retrieval, spacing, and interleaving at the appropriate time.

Retrieval is using questions and activities to test previously taught skills. Spacing is spreading out the skills over a period of time, where you return to the skill regularly.

So you cover 2 v 1s every three sessions. Interleaving is mixing up training, so you might be doing passing for 10 minutes, then rucking, then tackling, before returning to the passing exercise and developments.

These can be tricky to implement well (Perry et al., 2021), and considering players’ motivation may be important too (Bjork & Bjork, 2020).

3 PLAYERS DON’T LEARN WHAT YOU TEACH THEM

Everyone’s prior knowledge is different, and you can only understand new information in relation to what you already know.

Therefore, players learn their interpretation of what you teach them.

That means you should employ the cycle of checking what players know, linking new material to what they know and reviewing what they have understood. Avoid the closed questions to check, though. Instead, it is better to ask a player to explain what skills mean and when they would use them. Even better, get them to demonstrate it. This can be quite revealing and not always in a good way!

However, there are some common misconceptions players have. Through trial and error, we could discover common misconceptions that players are prone to or look out for and practise how to overcome them.

4 WHAT LOOKS LIKE A GENERIC SKILL LIKE DECISION MAKING IS ACTUALLY UNDERPINNED BY LOADS OF DOMAIN KNOWLEDGE

There’s no one decision-making area of the brain that makes all the decisions. We use our knowledge of a topic to make the decision.

So, try this. Can you set up a game for ice hockey to make more shots on goal when you have an overload in attack.

Sure, knowing generically what decision-making means helps, but the quality of your decision on the activity to use depends upon the knowledge you have about ice hockey.

The skill cannot be divorced from the content.

Coaching sessions that treat decision-making as a generic process, devoid of the specific knowledge we want players to actually make decisions about, are unlikely to be helpful.

Build domain knowledge and get them to practise applying it in these different ways.

For more from Sarah Cottingham, visit her website.

REFERENCES

Daisy Christodoulou’s (2019) blog daisychristodoulou.com/2019/04/what-the-marathon-teaches-you-about-education/

Bjork, R. A., & Bjork, E. L. (2020). Desirable difficulties in theory and practice. Journal of Applied research in Memory and Cognition, 9 (4), 475-479.

Perry, T., Lea, R., Jørgensen, C. R., Cordingley, P., Shapiro, K., & Youdell, D. (2021). Cognitive Science in the Classroom. London: Education Endowment Foundation (EEF). The report is available from: educationendowmentfoundation.org.uk/evidence-summaries/evidencereviews/cognitive-science-approaches-in-the-classroom/

Related Files

Newsletter Sign Up

Coaches Testimonials

Gerald Kearney, Downtown Las Vegas Soccer Club

Paul Butler, Florida, USA

Rick Shields, Springboro, USA

Tony Green, Pierrefonds Titans, Quebec, Canada

Subscribe Today

Be a more effective, more successful rugby coach

In a recent survey 89% of subscribers said Rugby Coach Weekly makes them more confident, 91% said Rugby Coach Weekly makes them a more effective coach and 93% said Rugby Coach Weekly makes them more inspired.

Get Weekly Inspiration

All the latest techniques and approaches

Rugby Coach Weekly offers proven and easy to use rugby drills, coaching sessions, practice plans, small-sided games, warm-ups, training tips and advice.

We've been at the cutting edge of rugby coaching since we launched in 2005, creating resources for the grassroots youth coach, following best practice from around the world and insights from the professional game.