Coach’s guide to cognitive load theory part 2

Overloading players with new information is not rare but does negatively impact learning. To help, try the scaffolding approach, writes Inner Drive’s Matt Shaw

In part 1, we looked at what Cognitive Load Theory is and how cognitive overload can impact your athletes’ learning.

Now, we are going to dig deeper into the science of learning to teach you the top techniques to reduce cognitive overload for your athletes and enhance their understanding, which will transfer into their game play.

RECAP - PART 1

As we discussed Part 1 (see link at bottom), Cognitive Load Theory emphasises the limited capacity of the working memory.

This means that, when teaching our athletes new skills or giving them new pieces of feedback, we must be careful to not overload them with too much information.

If we do, it can slow down and hinder the learning process and have a negative impact on the transfer of information to the long-term memory.

It is our job to make sure this does not happen to our athletes. So, what can we do to overcome this? Scaffolding is the solution.

WHAT IS SCAFFOLDING IN THIS CONTEXT?

Scaffolding is where you gradually remove support as your athlete begins to progress.

This could look like giving a player less feedback on their spin pass as they correct their errors themselves. It helps athletes to learn independently and manage their load.

The concept of scaffolding was developed by famous psychologist Lev Vygotsky.

He believed that, to learn effectively, learners should be guided by those with more knowledge in the field, or ‘experts’, to make sense of the material they are engaging with. There is a shift in responsibility during the learning process from coach to athlete.

The temporary support that scaffolding provides helps players reach higher levels of understanding and skill acquisition they would not be able to achieve without assistance. Coaches facilitate the gradual mastery of a concept or skill.

THE BENEFITS OF SCAFFOLDING

There are many reasons why scaffolding is an effective coaching technique. Here are a few:

- It enables athletes to achieve goals independently

- Athletes can use the knowledge they gain in training to apply to a range of competitive situations

- It can reduce negative emotions athletes experience when attempting a difficult task, such as feeling demotivated and discouraged

- It can keep your athletes focused and motivated

- Athletes will view incorrect answers as an opportunity to maximise their learning.

DIFFERENT PLAYING LEVELS MEANS DIFFERENT LEARNING LEVELS

Beginner and elite athletes have different skillsets and levels of experience, so why do we expect them to learn the same way?

This is where the Expertise Reversal Effect starts to come into play. It is based on the idea that novices do not learn the same way that experts do. The good thing about scaffolding is it caters towards this.

What is great about this method is it can be used on learners of all levels. A beginner may need more support whereas an elite athlete may need less. You can use it to offer different levels of support.

For novices, learning new information can be intimidating and overwhelming as they lack experience. Just imagine trying to teach a sliding tackle to a beginner while giving little to no input. It would be dangerous as well as very difficult for them to learn.

For this reason, the most effective way to teach novices is through explicit instruction and offering very structured support.

On the other hand, the most effective way to teach more advanced players is by giving them challenging tasks that allow them to draw upon their previous knowledge.

For example, if your player has mastered a standing tackle, then the next step would be teaching them a sliding tackle.

This is because they have already grasped the key concepts of a successful tackle and can draw upon their previous knowledge of a standing tackle to help them execute this new skill.

SCAFFOLDING AT DIFFERENT LEARNING STAGES

What is beneficial for beginners may be counter-productive for experts, so it is important to scaffold at different levels.

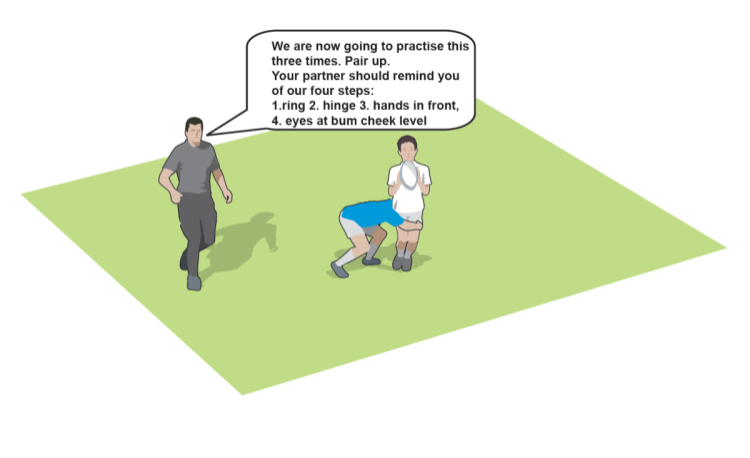

Beginners benefit greatly from worked examples. When coaching, try showing your athletes visual representations of a skill being successfully completed.

For example, if you wanted to demonstrate how to perform a pop pass effectively, showing a video or working through the steps would be a great way to do this.

Intermediates benefit from completion tasks. They are only completed partially; the athlete can then complete the rest of the task themselves. An example of this is an athlete having the coach drop the ball when performing a drop kick, but then having to drop the ball themselves afterwards.

Experts benefit from independent tasks. Skills are in their long-term memory, allowing more space in their working memory to help them solve problems.

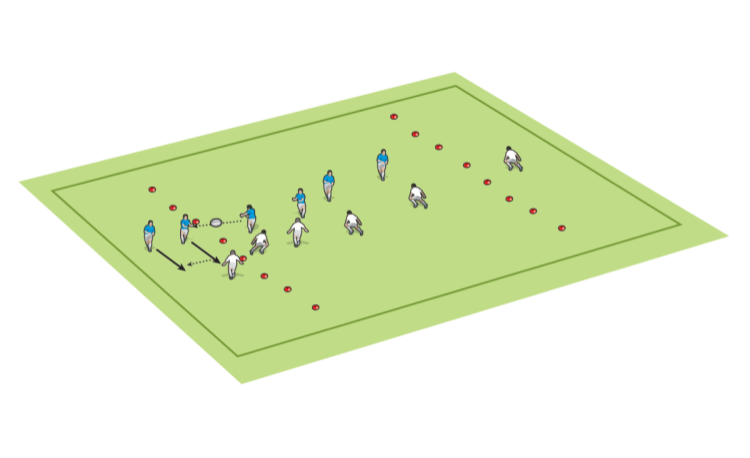

Allowing them to independently problem-solve drills while still being available when they need help will contribute positively to their expertise. This could look like having an athlete aim to score a try in training with multiple defenders chasing them down from different angles, while you watch and assess their technique from the sidelines.

This method of coaching is very beneficial because it provides athletes with enough structure so as not to overwhelm them at their current level, but still stretches them enough to expand their knowledge.With scaffolding, cognitive overload will soon be a thing of the past and your athletes’ learning will be enhanced.

Related Files

Newsletter Sign Up

Coaches Testimonials

Gerald Kearney, Downtown Las Vegas Soccer Club

Paul Butler, Florida, USA

Rick Shields, Springboro, USA

Tony Green, Pierrefonds Titans, Quebec, Canada

Subscribe Today

Be a more effective, more successful rugby coach

In a recent survey 89% of subscribers said Rugby Coach Weekly makes them more confident, 91% said Rugby Coach Weekly makes them a more effective coach and 93% said Rugby Coach Weekly makes them more inspired.

Get Weekly Inspiration

All the latest techniques and approaches

Rugby Coach Weekly offers proven and easy to use rugby drills, coaching sessions, practice plans, small-sided games, warm-ups, training tips and advice.

We've been at the cutting edge of rugby coaching since we launched in 2005, creating resources for the grassroots youth coach, following best practice from around the world and insights from the professional game.