How you can make practice perfect*

*Well, almost perfect. JORDAN CASSIDY, of SkilledAthleticism.com, discusses what makes a difference and how we can help players practise more effectively.

"Practice makes perfect"

"10,000 hour rule"

"Practice makes permanent"

"Practice, practice, practice"

"Perfect practice makes perfect"

Practice is crucial to becoming great at something.

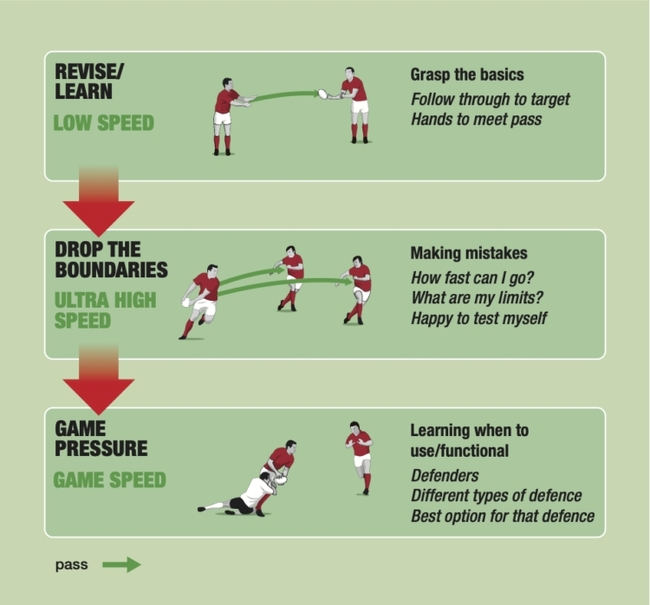

However, to improve, players could engage in numerous types of practice. These include:

Maintenance practice: Practising an aspect of performance that can already be performed.

Naive practice: Repetition after repetition.

Play practice: For fun and enjoyment.

Competition practice: Against an opponent.

Purposeful practice: Defined goals, monitoring, feedback and challenge.

Deliberate practice: Requires cognitive or physical effort, does not lead to immediate personal, social or financial rewards, and is done with the purpose of improving performance.

You know you have been involved in deliberate practice when the following happens:

- You have had to think hard and/or physically exert yourself.

- You have not done it for immediate gratification.

- You know you have done it to try to improve performance.

The theory of deliberate practice suggests that the amount of time an athlete engages in it determines their eventual attainment.

However, expert performers in sport have likely engaged in all of the different forms of practice mentioned above to get to where they are.

The main difference between these practices and deliberate practice is the targeting of specific, objective measures of performance, and the evaluation of practice. Hence, practice is deliberately planned to enhance performance.

What is difficult about deliberate practice?

There are three constraints that learners must overcome to engage in deliberate practice consistently.

Motivation

Performers must be primarily motivated to engage in practice to improve performance and not for some other reason, like enjoyment or social interaction.

Understanding players and their “why?” is critical. For example, do you know why they are coming to training?

Not all players will aspire to be elite performers. Some are playing for the social interactions with friends and peers, and some for the health benefits.

Your training sessions should align with these needs. Yet, you can still encourage those who want to focus on deliberate practice while others don’t.

Resources

At the start of a player’s sporting journey, parents’ interest aids the transition from initial playful involvement to more structured forms of deliberate practice.

Parents provide much of the financial resources to secure facilities for practice. This highlights the importance of educating and working with parents throughout a development program, like feeding children the right foods, transporting them to training and paying for the membership of various teams and clubs.

This helps put players on a level playing field when competing. But coaches must have empathy with players who are struggling for whatever reason.

Effort

Deliberate practice requires high levels of cognitive and physical effort. But it also requires rest.

The best training adaptations require a balance between the effort required to move the performer to the next level of skill and the rest required to recuperate from this high level of training effort.

It is a disservice to players if coaches embody an "always grinding" attitude. Rest and recovery are vital from a physical point of view to ensure adaptation occurs but also so learners can sustain deliberate practice to improve performance.

An organisation with greater resources and at a higher level can combine coach observations with video analysis of elite performers to better highlight the issue for the playing squad.

However, it is also important to note that in a school or grassroots environment players should not only practice deliberately. A school environment is an excellent place for learners to compete and play in various contexts, with sporadic exposure to practising intensely.

The A.S.P.I.R.E. framework for effective deliberate practice

You can use a six-step deliberate practice framework to work more effectively with your players.

It is called the ASPIRE framework - based around Analyse, Select, Practise, Introduce feedback, Repetition and Evaluate - and comes from the work of Ford and Coughlin.

- Step 1: Analyse how current experts in your sport perform key aspects of performance successfully, through observation, performance analysis or evaluation of scientific findings.

- Step 2: Select the aspect to be practised and then select or design the best methods, like tactics or techniques, for performing that key aspect successfully in your performance context, using information from step 1.

- Step 3: Design and run a practice in which the performer Practises the key aspect of performance using information from steps 1 and 2.

- Step 4: Monitor practice and Introduce feedback to the performer during and after practice on aspects related to goals set at step 2. Increase challenge, difficulty or complexity of the practice activity as athletes progress.

- Step 5: Include Repetition of the key aspect of performance, but do not exact repetition in all aspects of the practice. Ensure the practice is highly representative of the performance/competition environment where appropriate, with associated aspects of variability and context.

- Step 6: Evaluate current performance to determine whether, and to what degree, the key aspect of performance that required improvement has improved in relation to normative values.

See table below for a practical example.

Related Files

The differences between purposeful practice and deliberate practice are steps 1 and 6

|

1. Analyse |

Coaches notice that players are falling off left shoulder tackles (most players’ weaker sides). They have been looking at all the missed tackles and these are the most prevalent. |

|

2. Select |

The players tend not to lock into the tackle, so their shoulders aren’t tight to the ball carrier throughout the contact. |

|

3. Practice |

An exercise where the players used either shoulder randomly was set up. It was done at a walking pace to start with. |

|

4. Introduce |

The players watched each other as well as some clips of video footage shot on the coach’s phone. They noted the difference between a good tackle and a poor tackle and aimed to rectify it in the practice. |

|

5. Repetition |

The same activity was run for five minutes for the next three weeks. The speed and area were increased, depending on which players were progressing and which were still struggling. Eventually, it was run at game speed. |

|

6. Evaluate |

After four weeks, in a practice game, the tackling was assessed to see if players were tackling more effectively. This led to more work focusing on footwork before the tackle. |

The motivation is to improve tackle performance and players need to exert themselves as the practice adds pressure over the weeks, therefore moving from purposeful to deliberate practice.

Newsletter Sign Up

Coaches Testimonials

Gerald Kearney, Downtown Las Vegas Soccer Club

Paul Butler, Florida, USA

Rick Shields, Springboro, USA

Tony Green, Pierrefonds Titans, Quebec, Canada

Subscribe Today

Be a more effective, more successful rugby coach

In a recent survey 89% of subscribers said Rugby Coach Weekly makes them more confident, 91% said Rugby Coach Weekly makes them a more effective coach and 93% said Rugby Coach Weekly makes them more inspired.

Get Weekly Inspiration

All the latest techniques and approaches

Rugby Coach Weekly offers proven and easy to use rugby drills, coaching sessions, practice plans, small-sided games, warm-ups, training tips and advice.

We've been at the cutting edge of rugby coaching since we launched in 2005, creating resources for the grassroots youth coach, following best practice from around the world and insights from the professional game.