Oops, I did it again. The value of errors in the training process

Error-riddled training looks sloppy, and it is unlikely the players are learning much when all they do is make mistakes. But, there is value in making skill errors during the practice process. In this short explainer article, we will talk you through why errors matter, how many errors are reasonable in practice and how you can use skill errors as a skill-learning tool.

Error-riddled training looks sloppy, and it is unlikely the players are learning much when all they do is make mistakes. But, there is value in making skill errors during the practice process.

In this short explainer article, we will talk you through why errors matter, how many errors are reasonable in practice and how you can use skill errors as a skill-learning tool. Skills scientist Job Fransen explains.

When we practise, it is inevitable that we will make skill errors. Skill errors are errors in the production or the outcome of an intended skilled behaviour.

For example, a passing error can be both an error in outcome, that is the pass does not reach its intended target, and/or an error in the process, that is the passer uses an inappropriate movement pattern revealing the passing direction too early to an opposing player.

Errors are a vital part of the learning process of motor skills. When we practise a skill, we inevitably receive feedback on its outcome, like, did my pass reach its intended target? This feedback is reinvested into the learning process by either reinforcing successful behaviours or by adjusting one’s movements after an unsuccessful trial.

Using this trial-and-error method, learners develop the ability to detect and correct movement errors as they occur, leading to the learning of a motor skill. For example, a player who tackles another player can be successful or unsuccessful in stopping their progress or turning over possession.

- With each successful trial, the learner reinforces the behaviour used so it becomes more easily repeatable.

- With each unsuccessful trial, the learner considers what may have gone wrong and how it can be overcome on the subsequent trial. Perhaps the learner’s body position was too high, or they did not drive the legs enough after the tackle.

Eventually, a learner who explores the skill of tackling through both successful and unsuccessful attempts develops a strong understanding of the strategies that lead to successful tackling.

- Errors are a vital part of the learning process for motor skills, as they provide feedback for learners to reinforce successful behaviours or adjust movements after an unsuccessful trial.

- Using a trial-and-error method, learners develop the ability to detect and correct movement errors leading to the learning of a motor skill.

NOT ALL ERRORS ARE CREATED EQUAL

When it comes to learning a complex skill like scrummaging, making skill errors can be a valuable part of the process. But not all errors are created equal.

For novice players, it can be difficult and even dangerous to engage in unsuccessful scrummaging efforts. Additionally, novice players may not have the ability to detect and correct movement errors on their own accurately. In such cases, feedback from external sources, such as coaches or video analysis, plays an important role in helping the learner to self-detect and self-correct errors.

Often, the provision of feedback from these external sources can kickstart the learner’s path to self-detecting and self-correcting errors. As a result, coaches can gradually increase the degree to which a learner relies on their own intrinsic feedback mechanisms with increasing exposure to the learning of a specific skill.

There is a fine balance in practice design which manipulates the number of skill errors encountered. You need enough errors to strengthen intrinsic feedback mechanisms without facing a task which is too complex. If it is too complex and the players don’t understand how to use the errors.

- Not all errors are created equal when learning a complex skill like scrummaging.

- Novice players may need feedback from external sources like coaches or video analysis to accurately detect and correct errors.

- Coaches should balance the number of errors to strengthen intrinsic feedback mechanisms without overwhelming the learner with too complex information.

ERRORS AND EXPERTISE

The number of skill errors required to optimise learning has been a topic of skill acquisition research for some time. Some of this research has proposed there is an optimal task difficulty which depends on the skill level of the learner and the relative task difficulty.

In general, tasks we consider to be more complex have the potential to convey more information that can subsequently be used as feedback for players.

Additionally, players with a higher skill level typically require a higher level of task difficulty to optimise their learning. This is because they generally make fewer errors of smaller magnitude. They, therefore, require a higher level of task difficulty with the potential to convey more information, so the practice generates a sufficient amount of skill errors to challenge experts’ learning.

On the other hand, novices generally make more errors of a larger magnitude. As such, novice learners already make plenty of errors at relatively low task difficulties, which can then be used to strengthen self-detection and self-correction of skill errors.

For example, a novice player engaged in a 3 v 1 passing drill (in the context of rugby this can be considered to have a relatively low degree of task difficulty) is bound to make at least a couple of passing skill errors (for example, the pass goes behind the intended target or is intercepted by the defender).

While this task difficulty might suffice to elicit some degree of skill learning for novices, it is likely that experts in the same exercise make very few, if any, errors, which means their learning is not sufficiently challenged.

However, novice learners engaged in a highly complex task, like the running of tactical patterns of play, are likely to make many mistakes. The information they can perceive from this complex skill to potentially use as feedback to improve learning is simply too complex to be useful.

- The number of skill errors needed to optimise learning varies depending on the skill level of the learner and the task difficulty.

- Novices require lower task difficulty to make enough errors for self-detection and self-correction, while experts require greater task difficulty for more complex information to challenge their learning.

- Coaches can manipulate task difficulty and error rates to achieve specific practice goals like long-term learning, skill transfer, retention, or confidence building.

HOW MANY ERRORS?

We know a coach can manipulate the task difficulty of practice to challenge both skilled and unskilled players optimally. However, it is less clear how many errors should be made in practice in order to optimise learning. Yet, it seems intuitive to assume that error rates during practice depend on the aim of the practice session.

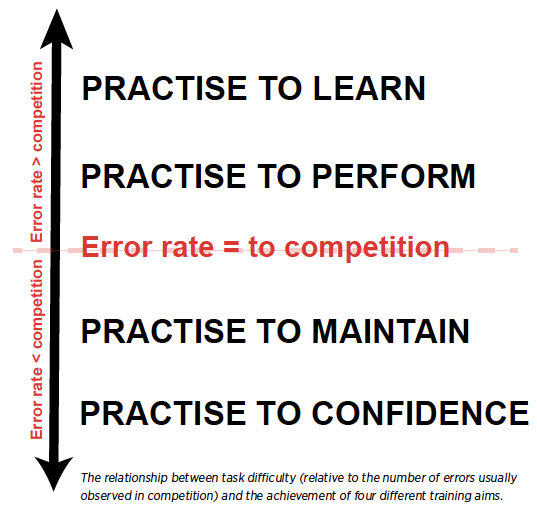

The illustration above shows how coaches can vary the number of skill errors in practice by manipulating task difficulty to achieve one of four practice aims:

- Practice aimed at encouraging long-term learning (practise to learn)

- Practice aimed at transferring skills to competition games (practise to perform)

- Practice to optimise the retention of behaviour over longer periods of time (practise to maintain)

- Practice to build confidence (practise for confidence)

Coaches can use the visualisation in the picture above to make sure the task difficulty of their practice matches their intended aims.

THE SPHERE OF COMFORT ANALOGY FOR INDIVIDUAL SKILL DEVELOPMENT

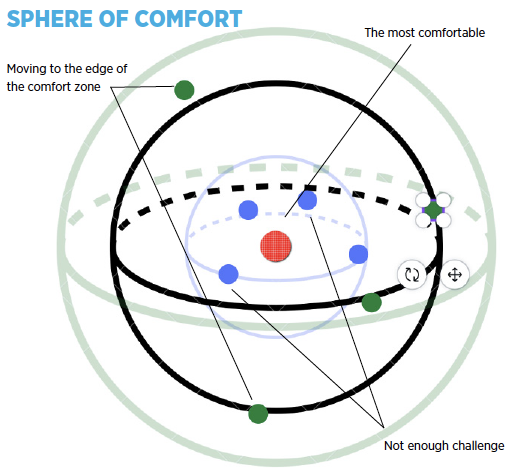

The "Sphere of Comfort" analogy illustrates how task difficulty can be used to develop an individual’s skills over time. Skill level as a sphere, with a practice close to the centre (red circle in the illustration above) representing comfortable tasks and practices farther away representing increasingly more challenging tasks.

Consistently practising within one’s comfort zone will decrease the size of the sphere over time (coloured blue in the illustration) while engaging in the practice of a task difficulty close to the edge of one’s sphere of comfort gradually expands the sphere (coloured green in the illustration).

Frequently challenging oneself is key to improving overall skill level. Coaches can use the ‘Sphere of Comfort’ analogy to ensure they provide sufficient challenges to individual players to optimise their skill development over time and maximise their skill potential.

DYNAMIC DIFFICULTY - USING SKILL ERRORS TO OPTIMISE LEARNING PRACTICE

Admittedly, it can be difficult for coaches to learn how to manipulate task difficulty to optimise learning. It may require significant knowledge of one’s players and their skill levels, as well as the predicted task difficulty of a range of exercises to do so.

However, there is a simpler method which is often referred to as practice with dynamical difficulty adjustments. Simply put, the concept of dynamic difficulty refers to the idea that the level of challenge or difficulty in practice can change over time. This is often done based on the success of previous trials.

A previous successful trial increases the task difficulty of the next trial, while an unsuccessful trial halts or regresses it. Dynamic difficulty stands in contrast to static difficulty, where the difficulty level remains constant throughout practice. A commonly known example of dynamic difficulty (at least for the first half of the task) is ‘around the world’ in basketball, where players advance to a position from which a shot is less likely to be successful after a successful trial but remain put when they miss. Dynamic difficulty is not only a useful tool for practice design, research also shows that it can increase player motivation and engagement.

We can easily apply dynamic difficulty to the context of rugby too. Imagine a kicker setting out a few kicking locations located around the left half of the field. Each time they score, they advance to a position with a smaller scoring angle, or further from the posts (or both), while when they miss, they regress back to the previous step. In doing so, the task difficulty automatically adjusts to the skill level of the learner, without much intervention from the coach.

However, using dynamic difficulty does not need to exclude the coach. In fact, dynamic difficulty is an important tool in the coach’s toolbox when it comes to designing sufficiently challenging practice, without the need to measure every little aspect and detail of practice.

Yes, this approach is not as precise as determining the optimal challenge level for each player individually, but it enables the implementation of practice that is close to the optimal level for a large group of players. See the example in the box within a specific training exercise aimed at exploiting passing to score a try on a small field.

The practical example of how task difficulty can be used to design practice so it adheres to the optimal challenge point theory should give you a better practical understanding of how task difficulty, challenge in practice, and error rates can be used to design practice that hits the sweet spot.

It is not so challenging that the athlete can no longer use their own senses to improve their performance trial-by-trial, and it is challenging enough to keep players motivated and engaged and offer them the right stimulus for long-term learning.

- Coaches can use dynamic difficulty adjustments in practice to optimise learning for a group of players, the level of challenge changes based on previous trial’s success.

- This approach is less precise than determining the optimal challenge for each player but enables the implementation of practice close to the optimal level for a group.

- An example of this is demonstrated in a rugby passing drill where task difficulty changes based on the number of successful trials and errors made.

Optimal Challenge Point:

Guadagnoli, M. A., & Lee, T. D. (2004). Challenge point: a framework for conceptualizing the effects of various practice conditions in motor learning. Links to an external site. Journal of motor behavior, 36(2), 212-224.

Hodges, N. J., & Lohse, K. R. (2022). An extended challenge-based framework for practice design in sports coaching. Links to an external site. Journal of Sports Sciences, 1-15.

Dynamic difficulty:

Zohaib, M. (2018). Dynamic difficulty adjustment (DDA) in computer games: A review. Advances in Human-Computer Interaction, 2018.

Related Files

Newsletter Sign Up

Coaches Testimonials

Gerald Kearney, Downtown Las Vegas Soccer Club

Paul Butler, Florida, USA

Rick Shields, Springboro, USA

Tony Green, Pierrefonds Titans, Quebec, Canada

Subscribe Today

Be a more effective, more successful rugby coach

In a recent survey 89% of subscribers said Rugby Coach Weekly makes them more confident, 91% said Rugby Coach Weekly makes them a more effective coach and 93% said Rugby Coach Weekly makes them more inspired.

Get Weekly Inspiration

All the latest techniques and approaches

Rugby Coach Weekly offers proven and easy to use rugby drills, coaching sessions, practice plans, small-sided games, warm-ups, training tips and advice.

We've been at the cutting edge of rugby coaching since we launched in 2005, creating resources for the grassroots youth coach, following best practice from around the world and insights from the professional game.