Performance feedback to boost development

In-session feedback is a powerful way to improve development and performance. It’s called augmented feedback and Chris Stabler explains here how to use it.

Augmented feedback is where you give feedback during a training session, particularly in the moment. It is different to feedback given after the session.

It allows the players to become active participants when improving their performance. The feedback can be instant, variable and adaptable to what is happening.

However, it is not suitable for every player. It is most effective when your players are in the associative/autonomous phase of learning.

That is when the players have begun to perform skills and movement patterns subconsciously or are beginning to link movement patterns with outcomes in a dynamic environment, such as playing in a game.

When to use it

Players receive intrinsic feedback when they have a good knowledge and experience of the game. Intrinsic means responses to how they feel, what they see and hear and their awareness of body movements.

Your ‘augmented’ feedback supplements that feedback. If they are still ‘learning’ the skill, it is harder for them to have that intrinsic feedback, and progression is likely to be coach-led, instructional and directive.

Let’s split the augmented feedback into two types:

- Knowledge of results: the outcome or result of the skill.

- Knowledge of performance: the process or performance of a movement or skill.

For example, if I were to give feedback on a player’s catching success during a training game, I might refer to the result or outcome by letting them know that they had four successful attempts but dropped three passes.

Alternatively, if I were to give feedback on the performance or process, I would let that particular player know that they dropped their hands towards their waist three times before receiving the pass, leading to a knock-on.

The player’s specific needs, the amount of knowledge and experience they have and their individual mindset should help to determine whether you should give feedback on the process, the outcome or a balance of both.

Four ways to use augmented feedback

Open questioning

When feeding back on a process or performance, open questioning allows the players to discuss what they felt, saw and heard, explaining what intrinsic feedback they were receiving in the moment.

Ask, for example: “When you realigned and held your depth and width before you scored, what did you notice compared to your previous attempt?”

Open questions allow players to express perceived challenges and possible solutions both pre- and post-activity and get them to reflect on their own intrinsic feedback.

Posed question

A posed question allows you to focus on specific aspects of technical and tactical performance. A good example is: "What if the opposition rushes up?".

Using question starters such as, "What if...?", "How might...?" or "Evaluate the impact of...", will allow players to think more deeply about processes and skill execution.

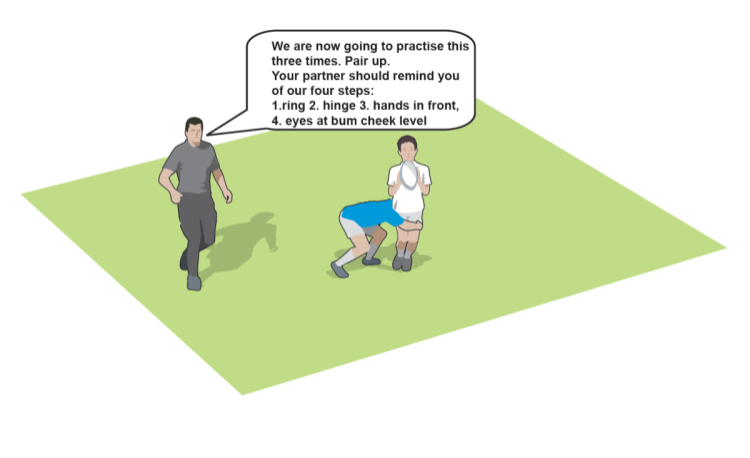

Quick technical prompts

Use quick prompts in a game situation to give the players some technical and tactical reinforcement while focusing on executing skills.

It’s a good check for players. For example, if we were playing a game with an attacking focus, we might use prompts such as ’depth check’, ’hip square’ or ’hands target’.

I will only use these prompts if I see several examples of poor execution within the game.

Depending on the level of experience of the players, I might involve them in deciding which prompts we use and ensure they fully understand exactly what is meant by each prompt.

I try to ensure I only use two or three prompts, to avoid feedback overload.

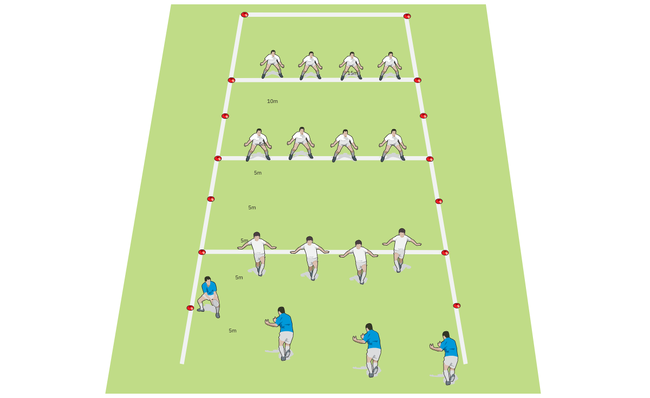

Freeze and rewind

Blow the whistle and the players freeze. You then pose an issue, allow the players to identify solutions and then, if necessary, allow them to reposition themselves for the play to continue.

It allows the players to either illustrate potential tactical choices or fault-correct.

It is important that this feedback lasts no longer than 20 seconds so that it doesn’t affect the game’s flow and allows players to correct faults.

Again, I only use this if I see the same examples two or three times within the game.

Related Files

tips on using augmented feedback

Be specific to the aim and outcomes of the session

Focus on the skills you want to improve and progress when giving feedback. Being concise will help the players focus on what aspects are essential within the session.

Feedback fatigue

Allow players time to practise and execute the technical and/or tactical skills to improve. This can be controlled by the feedback frequency, effectively choosing moments when to break from the game or practice into a huddle. If we focus on a specific performance aspect, the feedback time should be concise.

Timing

Consider which feedback technique you will use and at which point of the session. Could it be during a freeze frame as the skill is being performed or in a huddle at the end of a block of activity?

Using questions

Use questions to allow the players to consider their own feedback and promote self and peer analysis. Be careful to avoid the same player answering the questions or players just talking over each other. I tend to use a pass-on method or nomination method to ensure everyone has an opportunity for input.

Process or result?

I focus on the process of the skill execution rather than the outcome or results when coaching with the players who are developing. This will allow players ownership and an element of control, rather than to become fixated on an expected outcome that might not be met and be out of control – i.e., the environment and other players the task constraints.

Newsletter Sign Up

Coaches Testimonials

Gerald Kearney, Downtown Las Vegas Soccer Club

Paul Butler, Florida, USA

Rick Shields, Springboro, USA

Tony Green, Pierrefonds Titans, Quebec, Canada

Subscribe Today

Be a more effective, more successful rugby coach

In a recent survey 89% of subscribers said Rugby Coach Weekly makes them more confident, 91% said Rugby Coach Weekly makes them a more effective coach and 93% said Rugby Coach Weekly makes them more inspired.

Get Weekly Inspiration

All the latest techniques and approaches

Rugby Coach Weekly offers proven and easy to use rugby drills, coaching sessions, practice plans, small-sided games, warm-ups, training tips and advice.

We've been at the cutting edge of rugby coaching since we launched in 2005, creating resources for the grassroots youth coach, following best practice from around the world and insights from the professional game.