Reviewing the coaching process

If you've been on NGB coaching courses, you'll have seen the "How to Coach" skills key factors checklist. Let's review their relevance in a new age of smartphones and videos.

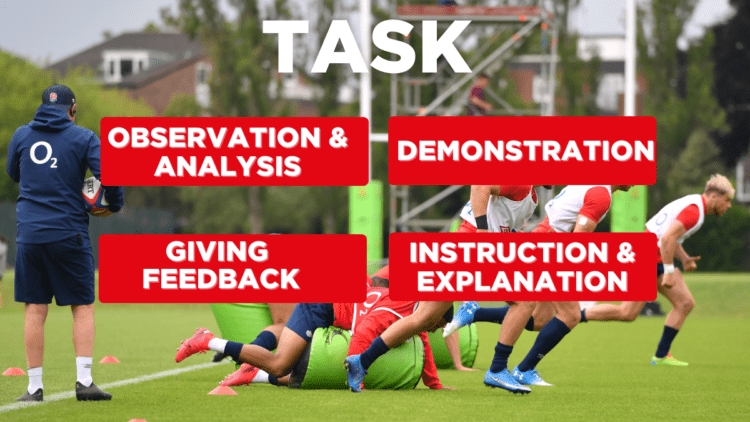

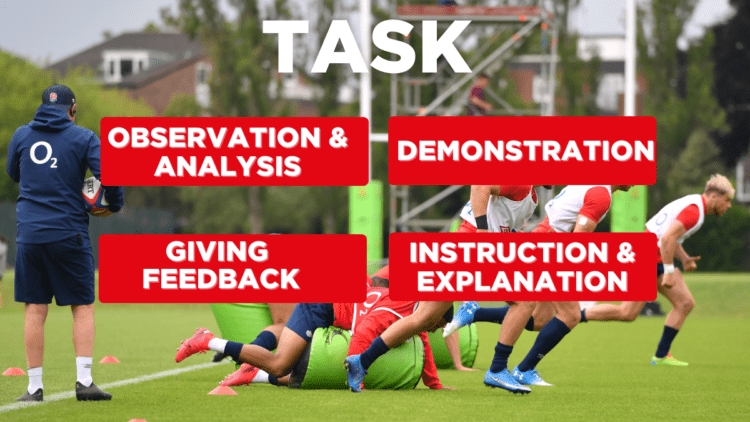

At the start of 2000, the world of coaching rugby began to formalise its understanding of the “How to Coach” skills. Experience was brought from across sport, under the leadership of the RFU’s Mark Harrington, to define the coaching process skills: the things a coach does to be effective, aside from technical knowledge.

Under the headings of Instruction and Explanation, Demonstration, Observation and Analysis, and Feedback, it was broken down into key factors to provide novice and expert coaches alike with a checklist for their coaching.

The work done then was ground-breaking for our sport and changed perceptions around good coaching. The SRU and WRU quickly followed and the UKCC coaching course for rugby had immediate impact.

I was reflecting on this evolution within coaching our sport and began to wonder if the same process skills are still relevant and, indeed, whether there are other process skills to be added for coaching 20 years on.

Has coaching the connected generation changed the coaching process skills?

We are still coaching human beings but is there a difference in how they want to be coached, and do the process skills need changing to reflect this?

“Instruction and Explanation” was broadly broken down into four key factors:

Questions to ask yourself before instructing and explaining might be around what the collective mood of the group is.

It is clear that our messages need to be even more focussed now. 20 seconds of speech from the coach is probably too long. Twitter type interventions are probably more effective, requiring detailed preparation and thought.

It is clear that our messages need to be even more focussed now. 20 seconds of speech from the coach is probably too long. Twitter type interventions are probably more effective, requiring detailed preparation and thought.

Visual explanation is better than verbal. When explaining, try referring to previous incidents and happenings, getting players to recall pictures of what could and should happen. In the world of the smartphone, a video of the practice rather than an explanation may be more effective, perhaps shared before the practice.

“Demonstration” was always a process skill that I struggled with. Should the coach demonstrate, should they get a player involved? Is there such thing as a perfect technique we should show to players?

My approach has always been to set the task, let the players have a go, and raise creative awareness by highlighting to the group individual solutions which might prompt them all to explore further.

The idea of a demonstration pre-activity, providing a model to copy is perhaps now less effective than a video sent pre-session, where the player can have a look at a range of ways of performing a task, and carry those images out onto the training pitch with them.

Observation and analysis too have changed. Technology means that there is much more potential for self-analysis by simply looking at actions on a smartphone.

The observation is recorded and accurate. There is no hiding place, no selective memory. The skill of the coach then becomes around asking questions to prompt self-analysis.

There is a whole new direction to follow here around understanding what a young player “felt” like at a particular moment, prompted by video.

For example, in a closed skill such as kicking, the player could be asked on watching a video “mark the follow through on that kick out of 10…. what would you need to do to improve on that score?”

For example, in a closed skill such as kicking, the player could be asked on watching a video “mark the follow through on that kick out of 10…. what would you need to do to improve on that score?”

In a more dynamic setting, perhaps a game, again asking the player to recall what they saw or how they felt can provide some real insight.

The Observation and Analysis model as developed also has a weakness as we move coaching on from solely being related to actions and more towards decisions made. We observe what happens around the ball, we analyse the actions of the ball carrier. How often do we look at the decisions made by ball carrier AND the support player? The temptation is just to analyse the physical action.

What about whether a good decision was made? Analysis of decisions made are arguably a more effective key to player improvement.

The final process skill was feedback. Clearly this is still a key skill for coaches and part of the coach’s armoury. Indeed, the way a player is given feedback is probably the key as to whether they accept that feedback.

Again, technology plays a part in feedback to players. However, trial by video is no fun for anyone. Technology can have great impact in generating self-feedback but only if the right questions are asked, and in the right way.

Nevertheless, for some time I have believed that in being sensitive in our feedback, in using a questioning approach without the balance of honesty, there is a danger feedback loses impact. Questioning that is too obtuse or too wide risks missing the point. Our fear of directness can lead to important points not being fully understood during a session.

Too many coaches are frightened of the direct statement “this is what I am seeing”, which should be followed by a question around “so what does this mean to what we are trying to do?” This approach ensures the player’s attention is focussed in a certain area before asking them to self-analyse in that area. It can then be followed by “now how will we change what is happening”.

The line of questions leads the player from

I cringe and my toes curl when I hear a coach ask, “How do you think that went?” thinking they are being supportive.

Are there any process skills to be added to the four identified that have been there for so long? Yes. Task and practice design, and progressions within those tasks are important parts of the coaching craft.

A cleverly designed practice can replace a thousand cleverly worded questions. A tweak to a constraint will take the players attention to explore a different area. A change in one or more of the constraints in the game can provide opportunities for the feedback to come from the game; the observation and self-analysis to be prompted directly from the game without the coach being overtly involved.

The best learning is implicit learning. Task design should be outcome based, preferably a decision-making outcome emanating from a Principle of Play.

There must also be a coaching process skill around setting a positive learning environment. These include:

I know that having too many process skills risks over-complicating what is essentially a craft, not an art or a science.

Coaching is a craft, and coaches are craftsmen and women. Much of what we do comes from instinct, authenticity, and our life script.

I know that by analysing these skills and calling them “process skills” we risk losing the magic of coaching.

My coaching has always been principles based rather than too much detail. Perhaps it would be better to call these skills “Principles of Coaching”.

At the start of 2000, the world of coaching rugby began to formalise its understanding of the “How to Coach” skills. Experience was brought from across sport, under the leadership of the RFU’s Mark Harrington, to define the coaching process skills: the things a coach does to be effective, aside from technical knowledge.

Under the headings of Instruction and Explanation, Demonstration, Observation and Analysis, and Feedback, it was broken down into key factors to provide novice and expert coaches alike with a checklist for their coaching.

The work done then was ground-breaking for our sport and changed perceptions around good coaching. The SRU and WRU quickly followed and the UKCC coaching course for rugby had immediate impact.

I was reflecting on this evolution within coaching our sport and began to wonder if the same process skills are still relevant and, indeed, whether there are other process skills to be added for coaching 20 years on.

Has coaching the connected generation changed the coaching process skills?

We are still coaching human beings but is there a difference in how they want to be coached, and do the process skills need changing to reflect this?

INSTRUCTION AND EXPLANATION

“Instruction and Explanation” was broadly broken down into four key factors:

- Plan what you will say.

- Gain their attention.

- Keep it simple.

- Use questions to check for understanding.

Questions to ask yourself before instructing and explaining might be around what the collective mood of the group is.

- Who in the group is feeling good, who is not feeling so good?

- Does the group need energising, or calming?

It is clear that our messages need to be even more focussed now. 20 seconds of speech from the coach is probably too long. Twitter type interventions are probably more effective, requiring detailed preparation and thought.

It is clear that our messages need to be even more focussed now. 20 seconds of speech from the coach is probably too long. Twitter type interventions are probably more effective, requiring detailed preparation and thought. Visual explanation is better than verbal. When explaining, try referring to previous incidents and happenings, getting players to recall pictures of what could and should happen. In the world of the smartphone, a video of the practice rather than an explanation may be more effective, perhaps shared before the practice.

DEMONSTRATION

“Demonstration” was always a process skill that I struggled with. Should the coach demonstrate, should they get a player involved? Is there such thing as a perfect technique we should show to players?

My approach has always been to set the task, let the players have a go, and raise creative awareness by highlighting to the group individual solutions which might prompt them all to explore further.

The idea of a demonstration pre-activity, providing a model to copy is perhaps now less effective than a video sent pre-session, where the player can have a look at a range of ways of performing a task, and carry those images out onto the training pitch with them.

OBSERVATION AND ANALYSIS

Observation and analysis too have changed. Technology means that there is much more potential for self-analysis by simply looking at actions on a smartphone.

The observation is recorded and accurate. There is no hiding place, no selective memory. The skill of the coach then becomes around asking questions to prompt self-analysis.

There is a whole new direction to follow here around understanding what a young player “felt” like at a particular moment, prompted by video.

For example, in a closed skill such as kicking, the player could be asked on watching a video “mark the follow through on that kick out of 10…. what would you need to do to improve on that score?”

For example, in a closed skill such as kicking, the player could be asked on watching a video “mark the follow through on that kick out of 10…. what would you need to do to improve on that score?”In a more dynamic setting, perhaps a game, again asking the player to recall what they saw or how they felt can provide some real insight.

The Observation and Analysis model as developed also has a weakness as we move coaching on from solely being related to actions and more towards decisions made. We observe what happens around the ball, we analyse the actions of the ball carrier. How often do we look at the decisions made by ball carrier AND the support player? The temptation is just to analyse the physical action.

What about whether a good decision was made? Analysis of decisions made are arguably a more effective key to player improvement.

FEEDBACK

The final process skill was feedback. Clearly this is still a key skill for coaches and part of the coach’s armoury. Indeed, the way a player is given feedback is probably the key as to whether they accept that feedback.

Again, technology plays a part in feedback to players. However, trial by video is no fun for anyone. Technology can have great impact in generating self-feedback but only if the right questions are asked, and in the right way.

Nevertheless, for some time I have believed that in being sensitive in our feedback, in using a questioning approach without the balance of honesty, there is a danger feedback loses impact. Questioning that is too obtuse or too wide risks missing the point. Our fear of directness can lead to important points not being fully understood during a session.

Too many coaches are frightened of the direct statement “this is what I am seeing”, which should be followed by a question around “so what does this mean to what we are trying to do?” This approach ensures the player’s attention is focussed in a certain area before asking them to self-analyse in that area. It can then be followed by “now how will we change what is happening”.

The line of questions leads the player from

- “This is WHAT is happening” towards

- “So WHAT does that mean?” and finally to

- “NOW, WHAT will we do about it?”

I cringe and my toes curl when I hear a coach ask, “How do you think that went?” thinking they are being supportive.

NEW SKILLS

Are there any process skills to be added to the four identified that have been there for so long? Yes. Task and practice design, and progressions within those tasks are important parts of the coaching craft.

A cleverly designed practice can replace a thousand cleverly worded questions. A tweak to a constraint will take the players attention to explore a different area. A change in one or more of the constraints in the game can provide opportunities for the feedback to come from the game; the observation and self-analysis to be prompted directly from the game without the coach being overtly involved.

The best learning is implicit learning. Task design should be outcome based, preferably a decision-making outcome emanating from a Principle of Play.

There must also be a coaching process skill around setting a positive learning environment. These include:

- Meeting and greeting players

- The physical environment

- Appearing prepared as a coach

I know that having too many process skills risks over-complicating what is essentially a craft, not an art or a science.

Coaching is a craft, and coaches are craftsmen and women. Much of what we do comes from instinct, authenticity, and our life script.

I know that by analysing these skills and calling them “process skills” we risk losing the magic of coaching.

My coaching has always been principles based rather than too much detail. Perhaps it would be better to call these skills “Principles of Coaching”.

Related Files

Vol-2-Issue-020-N-Scott-reviewing-the-coaching-process.pdfPDF, 801 KB

Newsletter Sign Up

Coaches Testimonials

Gerald Kearney, Downtown Las Vegas Soccer Club

Paul Butler, Florida, USA

Rick Shields, Springboro, USA

Tony Green, Pierrefonds Titans, Quebec, Canada

Subscribe Today

Be a more effective, more successful rugby coach

In a recent survey 89% of subscribers said Rugby Coach Weekly makes them more confident, 91% said Rugby Coach Weekly makes them a more effective coach and 93% said Rugby Coach Weekly makes them more inspired.

Get Weekly Inspiration

All the latest techniques and approaches

Rugby Coach Weekly offers proven and easy to use rugby drills, coaching sessions, practice plans, small-sided games, warm-ups, training tips and advice.

We've been at the cutting edge of rugby coaching since we launched in 2005, creating resources for the grassroots youth coach, following best practice from around the world and insights from the professional game.