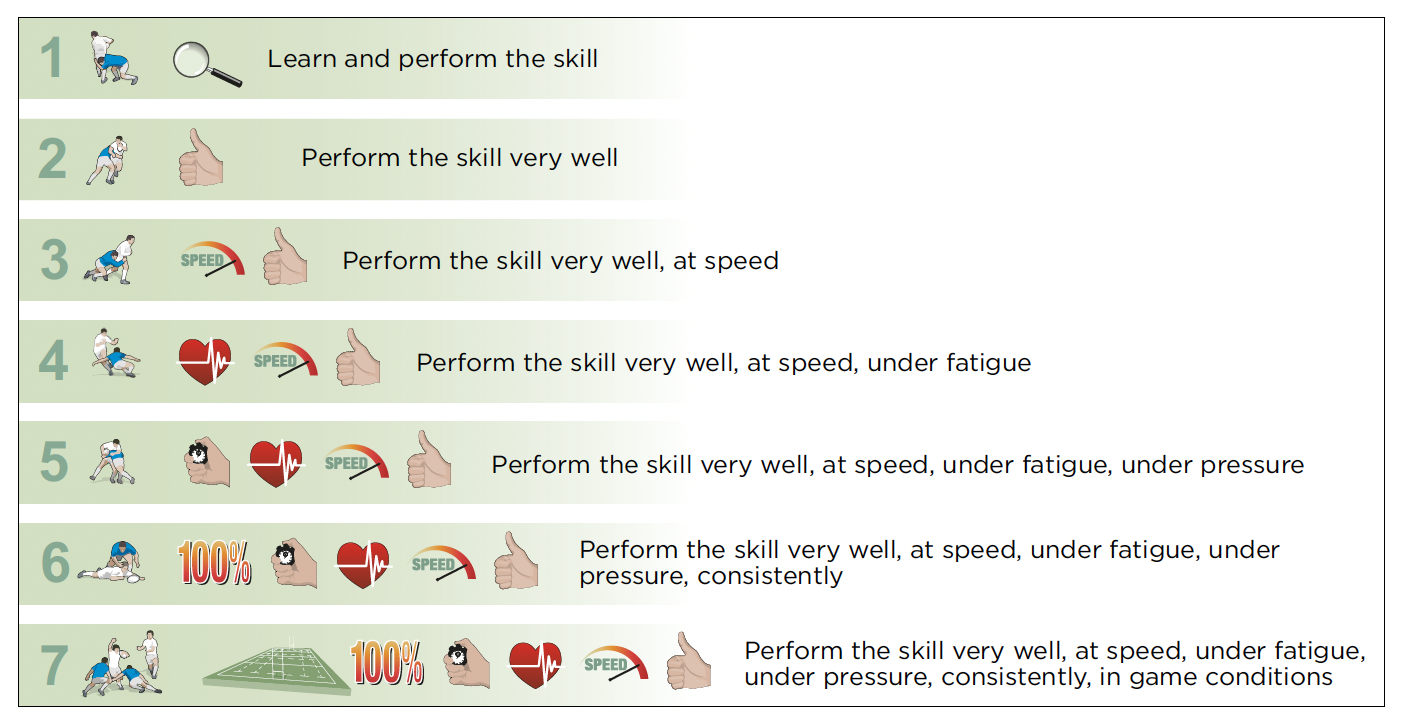

Seven skills steps to master in every sport

The layered approach to learning techniques that will help players repeat them in competition conditions. By sport performance consultant WAYNE GOLDSMITH

Just learning and mastering rugby skills is not enough.

It is no longer "practice makes perfect" or "perfect practice makes perfect" - the name of the game is performance practice.

Coaches and players must spend as much time, energy and effort learning to perform the fundamental skills of rugby in game conditions as they do on learning and mastering the basic skill.

Coaches should progress players systematically through the seven skills steps to ensure they can perform fundamental rugby skills in game conditions.

To do less than this is to rely on luck, the bounce of the ball and some good fortune - none of which are strategies for consistent success at any level of the game.

"It’s no longer ’practice makes perfect’ - the name of the game is performance practice..."

![]()

This is the first, and unfortunately for most players, the last step in their skills learning program.

Coaches come up with a drill, and players then copy it, try it, and learn it.

Skills mastery comes from regular practice, combined with quality feedback from coaches, and may incorporate the use of video and other performance analysis technologies - including the best one of all, the coach’s eye.

It is about here that most rugby coaches stop coaching the skill, believing that if the player can perform it really well, and it looks like it does in the rugby coaching textbooks, then they have done their job.

That couldn’t be more wrong. The skills learning job is not even 30% complete at this stage.

![]()

There aren’t many sports where the ability to perform skills really slowly is a winning strategy.

Technical perfection at slow speed may look great for the textbooks - but unless the skill can withstand game-level speed, accelerations, agility requirements and explosiveness, then the skill is not ’game-ready’.

Looking technically perfect at slow speed is great for the cameras - but it is even better for your opposition, who will have run around you and scored while you are receiving accolades for winning the "best-rugby-skills execution" competition. Try to play at a high tempo.

![]()

Think of the "danger zones" in all rugby games - the final five minutes before half time, the last 10 minutes of the game, the very last play.

Many games come down to the quality of skills execution in the last 5% of game time.

Being able to perform fundamental rugby skills when tired, dehydrated, glycogen depleted and suffering from neuro-muscular fatigue is a winning edge in all sports.

![]()

How many times do you see players miss simple targets, drop balls or make defensive errors at critical moments - the ’danger zones’ in games?

There is no doubt that emotional stress and mental pressure impacts on the ability of players to perform skills with quality and accuracy.

It is vital that rugby coaches incorporate the element of pressure in skills practices in training to ensure it is more challenging and more demanding than the competition environment you are preparing for.

Being able to perform the skill under game conditions once could be luck - but being able to do it consistently under game conditions is the sign of a real champion.

Consistency in skills execution in games comes from the consistency of training standards in preparation.

Adopting a "no-compromise" approach to the quality of skills execution and practices at training is a sure way to develop a consistent quality of skills execution in competition conditions.

Unfortunately, many players have two brains. One is the ’training brain’, which players use in practice - this ’brain’ accepts laziness, inaccuracy, sloppiness and poor skills execution in training, believing "it will be okay on the day" when they play a game.

The second is the ’game brain’, which they use on gameday. The secret to playing success is to use this brain in every training session.

![]()

This is what it is all about. The real factor in what makes a champion player is their capacity to perform consistently in game conditions.

Learning to perform a basic rugby skill well is not difficult. But add the fatigue of 75 minutes of tough competition, the pressure of knowing the whole season is on the line with the next scoring opportunity, the expectations of the board, coach, management, team-mates and tens of thousands of fans and all of a sudden that basic skill is not so basic: it becomes the equivalent of juggling six sticks of dynamite.

SUMMARY

The fundamental element of all sports is skill. Learning, practising and mastering the basic skills of sport is one of the foundations of coaching and sports performance.

However, just learning the skill is only the first step in the process. Only fools believe that "practice makes perfect" if the goal is to win in competition.

Players generally do not fail because their skill level is poor: they do so because their ability to perform the skill in competition conditions is poor. That is a coaching issue.

There is a huge difference between merely learning a skill and learning to perform the skill consistently well at speed, when you are fatigued, under pressure and trying to execute it in front of thousands of people.

PERFORMANCE PRACTICE

Performance practice is a logical, systematic seven-step process that takes players from learning the execution of a skill to being able to perform it under game conditions.

Let’s look at a relatively simple rugby skill - catching a high ball - and how it can be progressed through the seven skills steps as described above:

- Step 1: Teach the basic skill of catching a high ball – body position, head position and basic ball catching technique.

- Step 2: Master the skill of catching a high ball through quality practices and intelligent repetition.

- Step 3: Add speed. Have the player run to a point on the field and catch a high ball, kicked high in the air by a coach or training partner. Time their efforts. Alternatively, have them commence their high-ball catching practice from a laying face-down position. Again, time their efforts.

- Step 4: Add fatigue. Have the player execute some repeated speed runs immediately prior to catching a high ball, like six 20m sprints on a 30-second cycle, immediately followed by catching a high ball.

- Step 5: Add pressure. In addition to step 4, have two or three other players from the team (wearing padding if possible) run towards the player catching the high ball and bump and jostle them as they attempt to catch the ball.

- Step 6: Add consistency. In addition to step 5, have the player repeat the pre-fatigue sprints and attempt to catch the high ball five times while under pressure from team-mates, noting the effectiveness of their catching technique under fatigue and pressure conditions. Include a scoring system where the player is awarded points out of 10 for the quality of their skills execution with the onset of increasing fatigue and pressure.

- Step 7: There are two parts to coaching this step - training and playing.

In training, coaches working this step should be creative and develop practice activities which closely replicate and simulate game conditions, including a variety of practices to engage and stimulate the player’s learning, for example:

- Put the ball in a bucket of water before each high kick to test players’ ability to catch a high ball in wet conditions.

- Have the player catch the high ball from a variety of positions on the field. Also vary the position on the field from where the ball is kicked.

- Perform the practice at night to teach the player to catch a high ball under lights .

- Perform the practice with the player facing the direction of the sun to teach them to catch a high ball with restricted vision.

- Alternate the practice with the player facing the opponents’ try line and their own try line, so the player learns to take a high ball facing in any direction.

- Use combinations of the above. For instance, catching a wet ball at night while facing away from their own goal line.

The aim of coaching at this skills step is to prepare the player to be able to execute the skill in game conditions and to be able to meet the challenges and demands of every situation they face in a game.

The final aspect of the process is to observe and measure the player’s execution of the skill in actual games.

It is vital that, having worked with the player through skills steps 1-7, the coach provides detailed feedback on the player’s skills execution - ideally as soon as possible after the game.

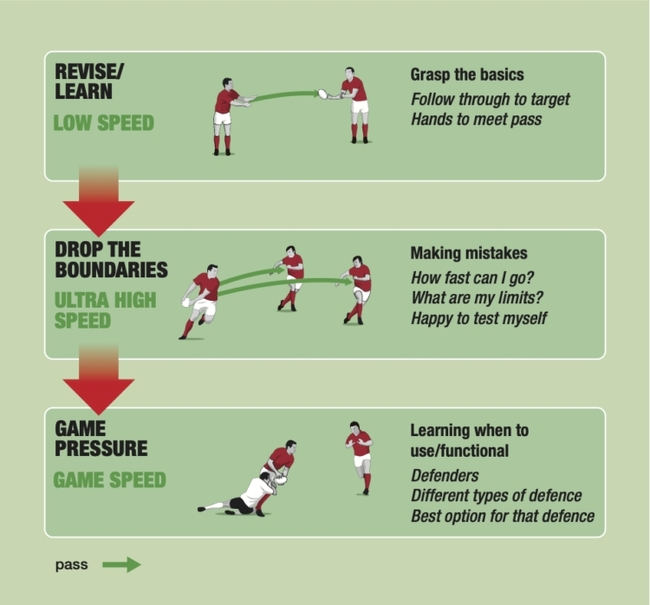

PRACTICE DOES NOT MAKE PERFECT

People used to say "practice makes perfect". We now know that is not the case.

Some people moved on and said, "perfect practice makes perfect". That is only true if the goal is to perform skills well for the textbooks.

The real maxim now is "performance practice makes for perfect performance". Practice consistently under the conditions to be experienced in competition and success will follow.

Related Files

Newsletter Sign Up

Coaches Testimonials

Gerald Kearney, Downtown Las Vegas Soccer Club

Paul Butler, Florida, USA

Rick Shields, Springboro, USA

Tony Green, Pierrefonds Titans, Quebec, Canada

Subscribe Today

Be a more effective, more successful rugby coach

In a recent survey 89% of subscribers said Rugby Coach Weekly makes them more confident, 91% said Rugby Coach Weekly makes them a more effective coach and 93% said Rugby Coach Weekly makes them more inspired.

Get Weekly Inspiration

All the latest techniques and approaches

Rugby Coach Weekly offers proven and easy to use rugby drills, coaching sessions, practice plans, small-sided games, warm-ups, training tips and advice.

We've been at the cutting edge of rugby coaching since we launched in 2005, creating resources for the grassroots youth coach, following best practice from around the world and insights from the professional game.