Slow ball plays

Editor Dan Cottrell adds further context to two sessions.

It’s easy to define the length of time before a ruck becomes regarded as slow. It is the length of time it takes for the defence to get reorganised.

At the top level, this is a matter of a few seconds, while at the lowest end of the game, it might not even happen at all.

So, these ’restart’ plays are only appropriate if you are faced with teams who organise their defences effectively.

In other words, they put in place players either side of the ruck and then spread out across the field.

Against this, try to run the ball any wider than three passes from the ruck and your team will be tackled a long way back from the gain line, with more chances of a turnover against you.

Though you could risk going wide, the most two realistic options are to kick or recreate quick ball.

Tactically, kicking away slow ball is risky – the defence is likely to be in position to deal with it. It’s always better to kick quick ball.

You can see that you are probably down to one option – create quick ball – which nearly always means that defenders are out of position.

The most dangerous quick ball is when you are going forward, too. That means you are getting over the gain line, so defenders must go backwards before they can re-position themselves for the next play.

While we would love to be able to penetrate the line with every play, that’s not always possible. But a good dent makes a difference.

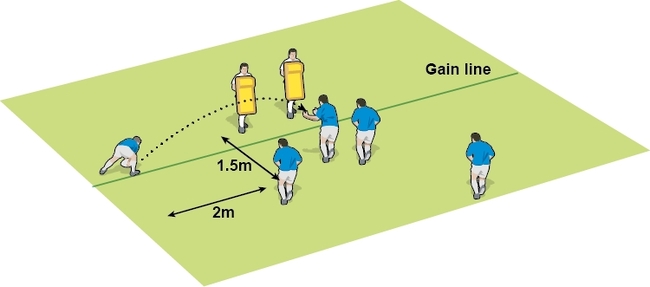

This means the ball carrier at least meets the opposition on the gain line, and, with good footwork, might be able to steal half a metre. Some sides use a ’latch’, where the ball carrier is driven through the gain line.

Whichever one you prefer, you need to have at least one, but preferably two, support players close by to deal with the threats to the ball. That’s why it takes a little bit of organisation.

You can use this session to improve your play in this area.

Essentials

- A short, fast and flat pass from the base of the ruck

The ball must be in the air for the least amount of time, and as close to the gain line as possible so the receiver has less distance to travel. The more time in the air, the more chance the opposition has to be in position. It must be straight from the base and not picked up and then passed for the same reason. - Little or no run up from the receiver

The receiver moves forward with the pass, not before the pass. This removes some of the risks of timing. It also allows the receiver to be more balanced.

Ball placement - get busy

Regular readers will know how much store I put in excellent ball placement after the tackle. It makes rucking and continuity so much easier.

The mindset should be that you transfer the ball securely, no matter whether you are in open play, or on the ground after the tackle.

In the latter example, a lot of ball placement comes down to the ability of the player to manipulate their body. This has three main outcomes:

- Shifting the body so the ball can be placed as far away from the opposition as possible.

- Shifting the body and the ball to make it more difficult for the opposition to grab the ball, as it’s a moving target.

- A whole body movement is more stable and secure than just manipulating the ball with the arms.

Therefore, ground work is an essential part of any ruck session.

For the youngest, less developed players, this isn’t always easy.

In my experience, a short, sharp session in this area is best, and certainly not when the weather is cold, or the ground wet.

Whatever the age group, falling and keeping two hands on the ball works as an excellent way to make a safe and effective contact with the ground.

The players can turn their shoulders and lower body, rolling and twisting, while always maintaining ball security.

These exercises are some of my favourites.

Make sure you go from unopposed to opposed, so the ball carrier gets a sense of the speed they can place the ball, and how effective their body manipulation is.

Put these into touch-type games, where the touched player has to go to ground and present the ball accurately.

Any deviation from the best technique should lead to a turnover. The players will soon work hard to ’transfer’ secure ball.

Related Files

Newsletter Sign Up

Coaches Testimonials

Gerald Kearney, Downtown Las Vegas Soccer Club

Paul Butler, Florida, USA

Rick Shields, Springboro, USA

Tony Green, Pierrefonds Titans, Quebec, Canada

Subscribe Today

Be a more effective, more successful rugby coach

In a recent survey 89% of subscribers said Rugby Coach Weekly makes them more confident, 91% said Rugby Coach Weekly makes them a more effective coach and 93% said Rugby Coach Weekly makes them more inspired.

Get Weekly Inspiration

All the latest techniques and approaches

Rugby Coach Weekly offers proven and easy to use rugby drills, coaching sessions, practice plans, small-sided games, warm-ups, training tips and advice.

We've been at the cutting edge of rugby coaching since we launched in 2005, creating resources for the grassroots youth coach, following best practice from around the world and insights from the professional game.