Test players’ testing for better outcomes

Studying strengths and weaknesses can help players outwit their opponents. DAN COTTRELL talks to AMY PRICE about incorporating this into your training.

"Players don’t test each other enough", says Amy Price, women’s national coach developer for the FA and coach developer for sports performance gurus Grey Matters.

"In a match situation, or in the training area, they should be probing and challenging their opposition number to work out how to outwit them. The best players know when and why to do it.

"Players with high levels of understanding recognise opportunities on the pitch to learn more about their opponents.

"Some tests can be higher stakes than others; however, there are plenty of low-stakes tests that will pay dividends in a competitive environment.

"We must encourage our players to see those opportunities, understand when to test them and how to use that information."

Outwitting at the right level

Outwitting an opponent is a critical factor in any bout.

It involves using strategic and tactical manoeuvring to gain an advantage. It’s important to break down the terms ’strategy’ and ’tactics’.

A strategy is a longer-term plan devised in advance of the event, which, in a team sport, is often based on what the team wants to do in and out of possession.

In a rugby context, it might involve when to kick or how to defend in certain parts of the field.

Tactical manoeuvring, though, is more about how the team or individuals respond in certain game situations under strong time constraints.

This takes into consideration team strategy, but is guided by game context, including player capabilities. So, based on the opposition and scoreline, it is about which move to use and then, within that, when to strike or when to pass.

It is essential to differentiate between having a strategy and thinking strategically.

The latter requires players to use their knowledge in-game to achieve team or individual goals in a flexible way. This means players are responsive to new information to find the most optimal way to outwit the opponent.

In a team sport, outwitting the opponent requires a combination of individual and team decisions. Yet, many teams lack metacognitive awareness of their outcomes – that is, being aware of what they know and what they don’t know.

Amy continues to challenge us to think about what our players are thinking.

"If the players aren’t noticing what the opponents are doing, they won’t know if their plans are working and when to tweak them," she says.

If a player breaks the line and offloads to another player to score, they are less likely to replicate this play later in the game if they can’t understand why it worked. Or, after this break, they might not recognise that the defence may be more aware of it themselves and aim to close this gap, thus creating a space in a different part of the field.

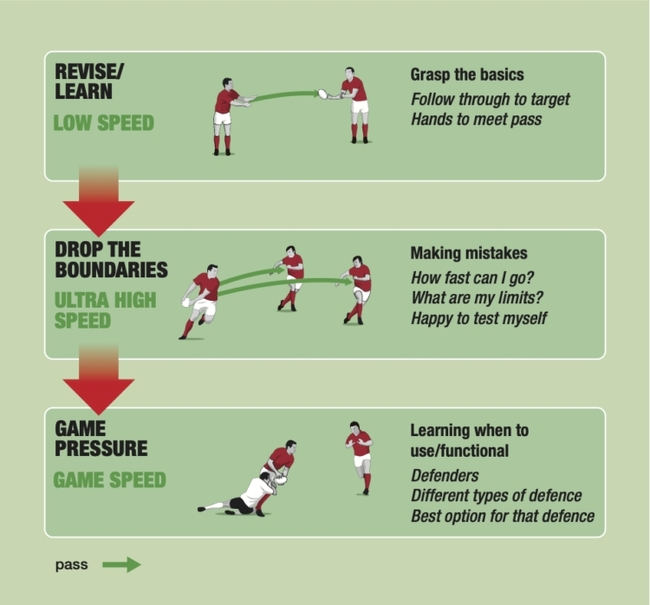

“Metacognitive skill is recognising opportunities to detect information using small tests,” says Amy.

“It is a low-stakes way of finding out where there are strengths and weaknesses without putting the team in a vulnerable situation.

"This means that players can test their direct opponent in moments where they are not throwing away a clear scoring chance or giving the opponent a clear scoring chance.

"In football, for example, a striker presses a defender to see what their ball skills are like in tight spaces."

Thank you for reading

to enjoy 3 free articles,

our weekly newsletter, and a free coaching e-book

Or if you are already a subscriber, login for full access

Newsletter Sign Up

Coaches Testimonials

Gerald Kearney, Downtown Las Vegas Soccer Club

Paul Butler, Florida, USA

Rick Shields, Springboro, USA

Tony Green, Pierrefonds Titans, Quebec, Canada

Subscribe Today

Be a more effective, more successful rugby coach

In a recent survey 89% of subscribers said Rugby Coach Weekly makes them more confident, 91% said Rugby Coach Weekly makes them a more effective coach and 93% said Rugby Coach Weekly makes them more inspired.

Get Weekly Inspiration

All the latest techniques and approaches

Rugby Coach Weekly offers proven and easy to use rugby drills, coaching sessions, practice plans, small-sided games, warm-ups, training tips and advice.

We've been at the cutting edge of rugby coaching since we launched in 2005, creating resources for the grassroots youth coach, following best practice from around the world and insights from the professional game.