When to use direct instruction

We all instruct as coaches at some stage of a training session. However, direct instruction is either overused or, in reverse, underappreciated. Here’s a guide on why and when to use it.

According to the Times Educational Supplement in 2018, “Instruction is widely misinterpreted … [Paul Kirchner] believes most teachers see it as ‘drill and skill, authoritarian, isolated fact accumulation, one size fits all’ when it is nothing of the sort.”

There is a strong movement towards the idea of minimal guidance by the coach. Yet, we need to know when we should directly instruct, and when that’s appropriate. It’s worth remembering that one style is not “better” than another, it’s just more appropriate in certain circumstances.

WHEN WOULD YOU USE DIRECT INSTRUCTION

- Giving the players some prerequisite knowledge to learn something else

- Giving a clear explanation of what is expected, and what you want them to do

- Providing a model of the process, showing how the skill or tactic is done, and talking through why you did it

KNOWLEDGE TO LEARN

When you are introducing a new skill or tactic, the players will need to have some prior knowledge. For example, when you are developing passing skills, the players will need to know why passing is important. Otherwise, they won’t make the connection to apply it in a game. As the skills become more complex, the player needs more prior knowledge..

You can ask the players about their prior knowledge or simply remind them. While asking players can be seen as inclusive, sometimes with a big group only a couple of players really engage and the others simply wait for the answer anyway. You could split the group into pairs and ask one of the pairs to ask the other pair for an answer to your question and then you could randomly pick on a pair. This has high engagement. However, it requires good group dynamics and plenty of practice at this technique to be most effective.

THIS IS WHAT WE WANT

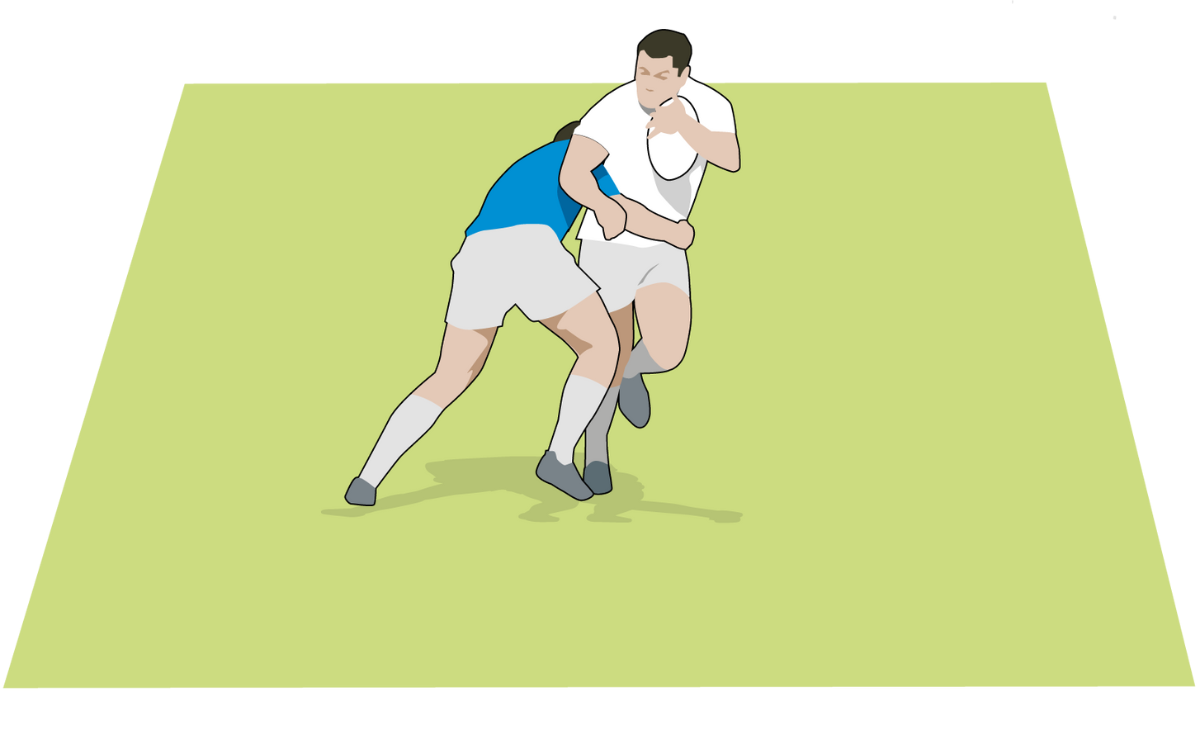

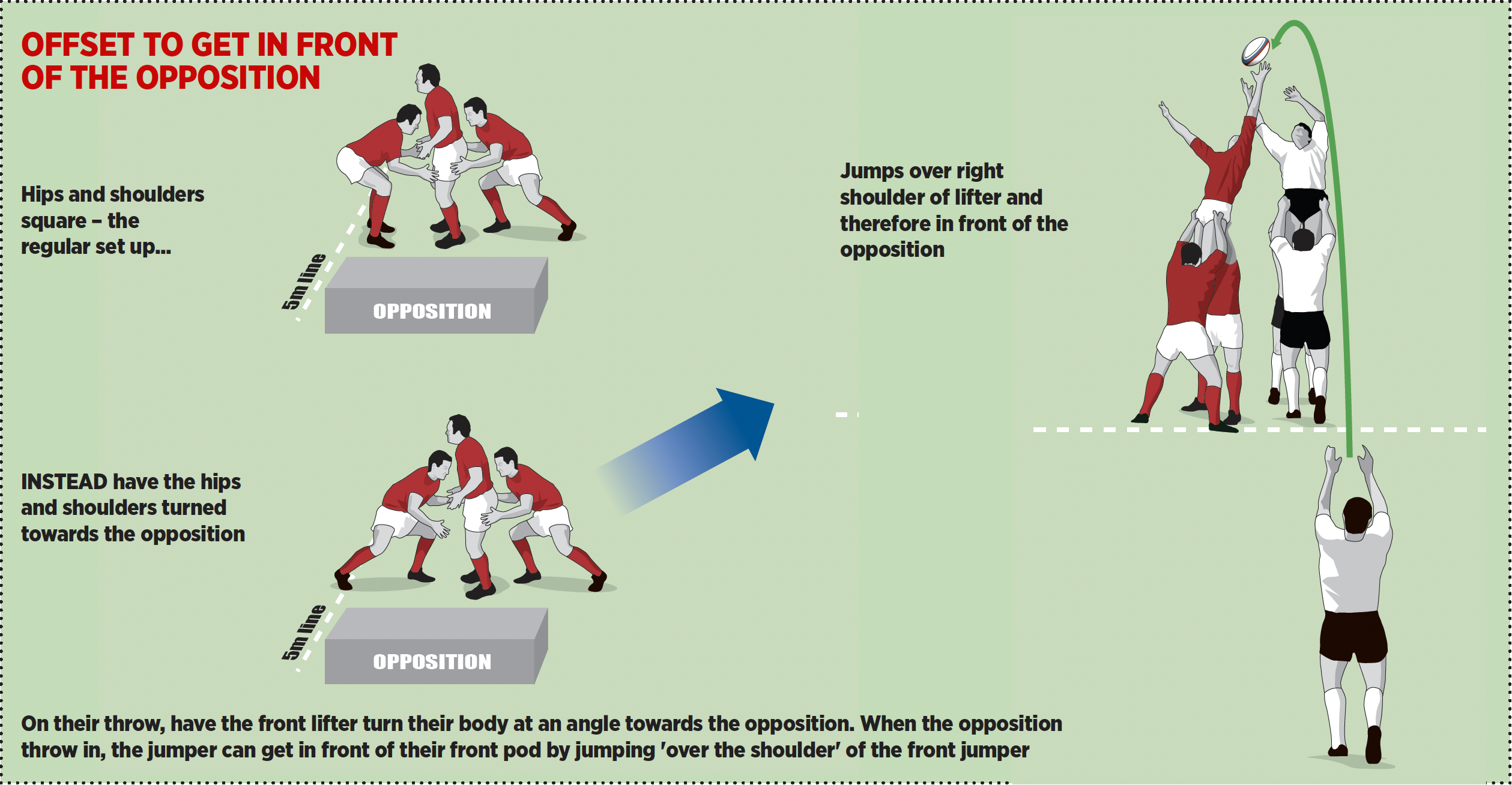

A complex or new skill can need an explanation. For example, when you introduce tackling, you will want the players to understand safe techniques and, in the activity, how the players will be interacting with each other. You might say: “Player A will be on their knees holding a ball. Player B will be next to them, with their head already on the back of the shorts. I want Player B to complete the tackle”.

The same would go for a new game. You will want to outline the goals of the game, like how to score and how to stop the other team scoring. You might also suggest some of the behaviours you want to see or remind them of some of the skills that they might want to use.

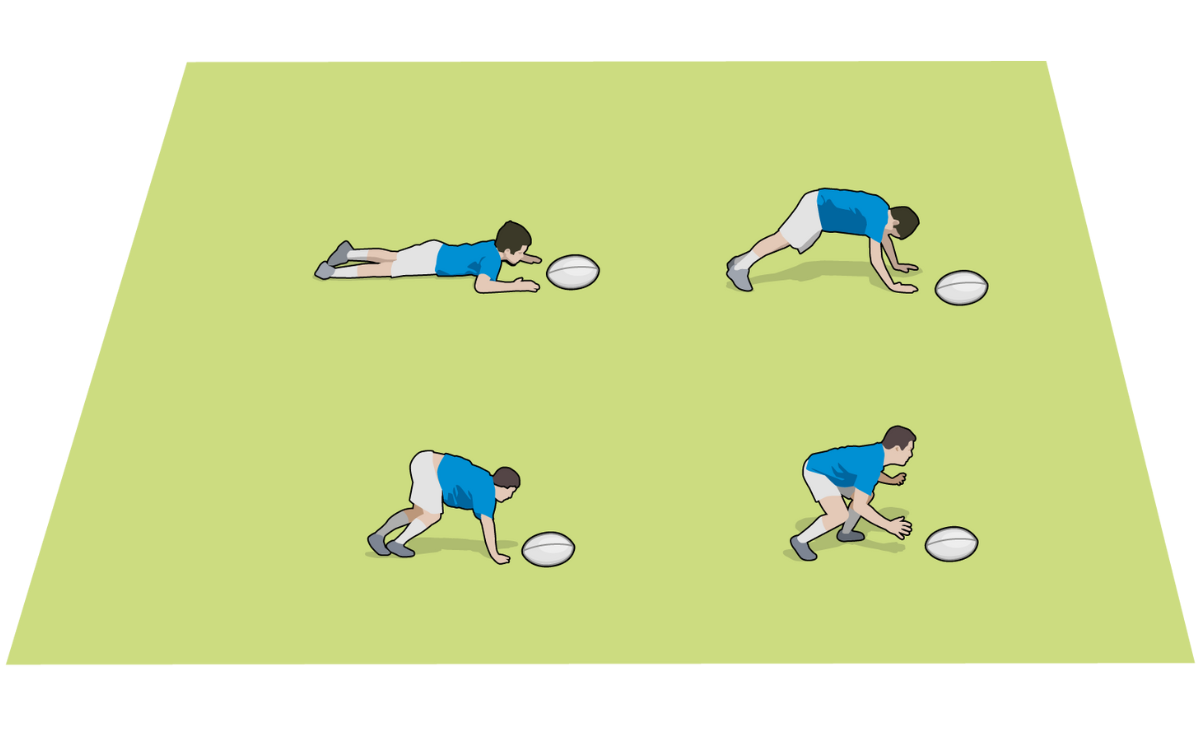

THIS IS HOW YOU DO IT

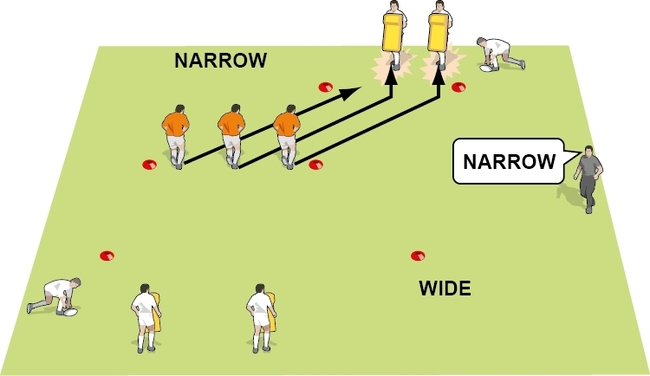

Modelling through demonstrations is a powerful way to help players solve problems faster. This is more applicable to movement patterns than decision-making situations. For example, if you want your players to pass more accurately with their weaker hand, you show them how to hold the ball, and then how you want them to finish with their hands.

You could equally do this through peer demonstration too, with one of the better players being used as a demonstration model. This form of peer learning is made more powerful by your interventions, either to confirm good practice or to make adjustments to the model.

As you are modelling, the player needs to understand why the model works, linking it to prior knowledge. For example, you will explain or remind the players that you want passes to move quickly and accurately in front of the target. Then, you will show them, or they will observe that the model allows this to happen.

DIRECT INSTRUCTION IS ACTION

Whatever the detail you need to explain, the players need to practise the instructions. They won’t improve if they just listen to you talking. Best practice suggests that you talk for no more than 30 seconds before letting the players take some form of action.

That’s a rule of thumb because you don’t want to rush what you say. However, it is a good proxy for the ratio of information to time spent. In other words, you should only try to give one piece of new information if possible.

For example, if you are setting up a game, ideally it is one the players have played already, so you will purely be adding to that game with one more piece of information. This could be a rule change, different numbers or different goals.

For more complex information, you will be doing a mix of direct instruction, with demonstrations, modelling and checking for understanding.

Then let the players play, have a go, make mistakes and solve the problems.

Thank you for reading

to enjoy 3 free articles,

our weekly newsletter, and a free coaching e-book

Or if you are already a subscriber, login for full access

Newsletter Sign Up

Coaches Testimonials

Gerald Kearney, Downtown Las Vegas Soccer Club

Paul Butler, Florida, USA

Rick Shields, Springboro, USA

Tony Green, Pierrefonds Titans, Quebec, Canada

Subscribe Today

Be a more effective, more successful rugby coach

In a recent survey 89% of subscribers said Rugby Coach Weekly makes them more confident, 91% said Rugby Coach Weekly makes them a more effective coach and 93% said Rugby Coach Weekly makes them more inspired.

Get Weekly Inspiration

All the latest techniques and approaches

Rugby Coach Weekly offers proven and easy to use rugby drills, coaching sessions, practice plans, small-sided games, warm-ups, training tips and advice.

We've been at the cutting edge of rugby coaching since we launched in 2005, creating resources for the grassroots youth coach, following best practice from around the world and insights from the professional game.