Take off rugby drill to jump higher

The main factor that determines how high we jump (apart from gravity) is our vertical speed at take-off. This in turn is determined by the way we generate that speed in the short time we have to "prepare" the jump.

The rugby coaching tips discussed in this article are based on a two-footed jump, but the principles also underpin the single-footed jump.

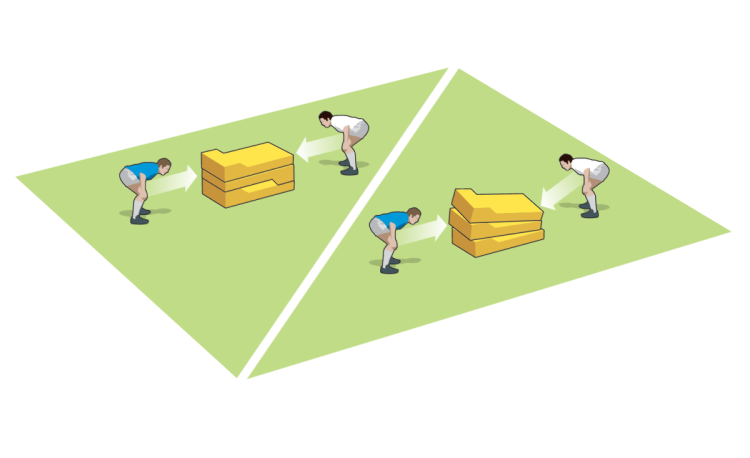

Preliminary step

The most influential factor in jumping for height is the use of the "counter-movement" principle, known as the "stretch-shorten" cycle. We see this as the step into a jump or as the backswing of the pass.

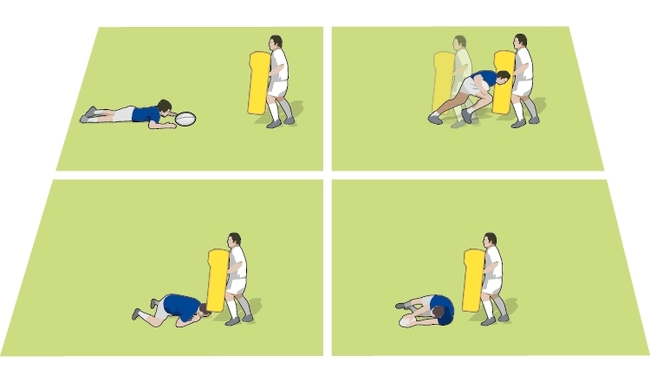

This "preliminary step" into the jump raises the player into the air, gravity pulls him down. As he lands his ankles and knees, and perhaps his hips, all flex to absorb the weight.

That flexing motion stretches the jumping muscles in the legs (the "extensor" muscles) as they work to stop the athlete collapsing. We call this "eccentric work".

Stopping that eccentric or stretching movement creates a powerful force in the muscles.

For a moment the jumping muscles are in "isometric mode", not stretching or contracting, just holding the player's weight and not releasing the force.

As they then begin to contract (do "concentric" work) the muscles rapidly apply the force to the ground, driving the jumper up into the air.

More force

As the graph above the picture indicates, eccentric work develops a much greater force than concentric work. In addition, this force is even greater at higher eccentric speeds.

The major benefit of this eccentric work is the increased rate of force development, which, along with other principles, leads to a greater take-off velocity.

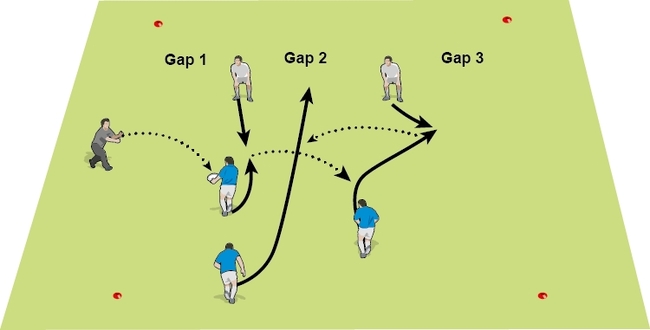

To get the greater eccentric speed, therefore, the player must jump higher in the preliminary step.

In most rugby situations this means either giving the opposition advance knowledge of your lineout intentions, or, in the open field, using time we usually won't have.

As with all applications, the biomechanics advantage must be traded off against the requirements of the game.

Less contact time with the ground

When a player goes through the counter-movement action (eccentric, isometric, then concentric work), there will be a relatively short time spent in contact with the ground after the preliminary step, that is between landing and then taking off again.

There is still some discussion on just how long "short" is, but without doubt the contact time should be less than 0.3 seconds.

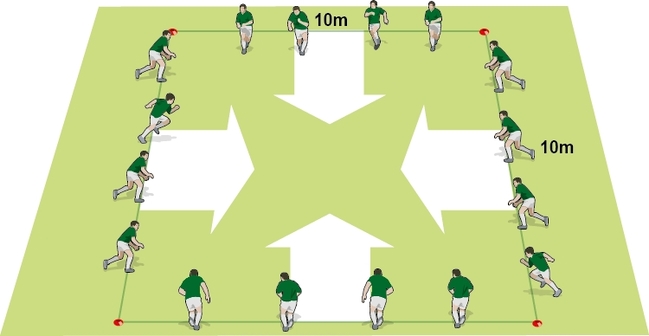

The best athletes gain the maximum jump from a ground contact time of around 0.2 seconds, and "bouncy" athletes will do that from a considerable drop height – up to 1 metre!

A good plyometrics programme with graduated drop heights starting at less than 30cm will develop that bouncy skill, an essential in the rugby environment.

Newsletter Sign Up

Coaches Testimonials

Gerald Kearney, Downtown Las Vegas Soccer Club

Paul Butler, Florida, USA

Rick Shields, Springboro, USA

Tony Green, Pierrefonds Titans, Quebec, Canada

Subscribe Today

Be a more effective, more successful rugby coach

In a recent survey 89% of subscribers said Rugby Coach Weekly makes them more confident, 91% said Rugby Coach Weekly makes them a more effective coach and 93% said Rugby Coach Weekly makes them more inspired.

Get Weekly Inspiration

All the latest techniques and approaches

Rugby Coach Weekly offers proven and easy to use rugby drills, coaching sessions, practice plans, small-sided games, warm-ups, training tips and advice.

We've been at the cutting edge of rugby coaching since we launched in 2005, creating resources for the grassroots youth coach, following best practice from around the world and insights from the professional game.